Today, I went to Bathurst to check out a fossil and mineral museum.

Bathurst reminded me of Bellingen, in that there were a lot of historic building-fronts paired with modern shops, which actually looks kind of weird. Especially when the place is bustling with cars – it becomes anachronism-stew! Have a look:

They even have old lampposts:

They had a line of these right in the middle of the road – the cars had to drive around them:

This was the museum – I kid you not:

And these were near the entrance, though I’m not sure why:

The entrance itself was almost hidden – it was a small gate at the side, almost too small to be public access, then you had to walk around the back of the building and enter through the rear. It really felt like they were testing to see how committed you were, but clearly I passed, because I’m making a blog post about it.

This was outside the entrance, to let you know you were on the right path:

Doesn’t look like much, does it? But this is the trunk of an agatised gum tree from about 20 million years ago, found in NSW. What does agatised mean, you ask? (And if you don’t, too bad, because I’m telling you anyway). Agatised is the cousin of opalised, except instead of being turned into opal, the fossil is turned into agate – like opal, it’s a variety of silica, but the crystal structure is different and it’s not as colourful.

A close-up, showing the agate:

Then it was into the museum! Except it’s not really an official museum – this is the private collection of Warren Somerville from Orange:

He’s still around, though he’s retired now. And it’s only about a quarter of his collection, the really good stuff. He field-collected a lot of these, but also traded and bought a lot of them as well, and eventually was given an honorary Professorship from Charles Sturt University.

The first part of the museum had some fossils, but mostly minerals – most of the fossils were in the back. But they had this neat-looking crinoid in mudstone, from the US:

They had this in a big case in the first room:

I was wondering what was so special about it, until I walked around the other side:

Oh. This is amethyst quartz from Brazil, in ‘vugh’. Vugh is just a small cavity in the rock, often lined with crystals, and I feel everyone should know about it because it’s a funny word – I mean, ‘vugh’ sounds someone with a bad cold trying to complain about it.

This is Manganoan Calcite, from deep in the Zinc Corporation Mine:

There was a vertical fracture in the rock where water flowed in a waterfall, depositing the calcite. Somerville bought this because it’s the largest, most colourful, and best-formed remains of a waterfall he’s ever seen.

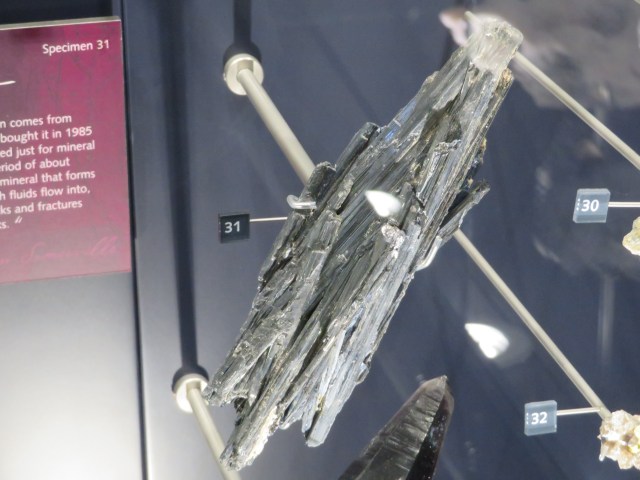

This is stibnite from the Hillgrove Mine:

I took that picture because it just looks so bizarre – more like pencil shavings than a naturally-formed mineral. Stibnite forms when hot, mineral-rich fluids flows into cracks and fractures and cools inside them.

Some more stibnite, still looking like nothing you’d find in nature:

But apparently, I don’t know much about nature, because those are all natural formations. Nature is weird.

This is crocoite, and more photos that I took just because they look bizarre:

Though in this case they look more like carrot sticks than pencil shavings. Apparently, Tasmania is a famous source of this mineral.

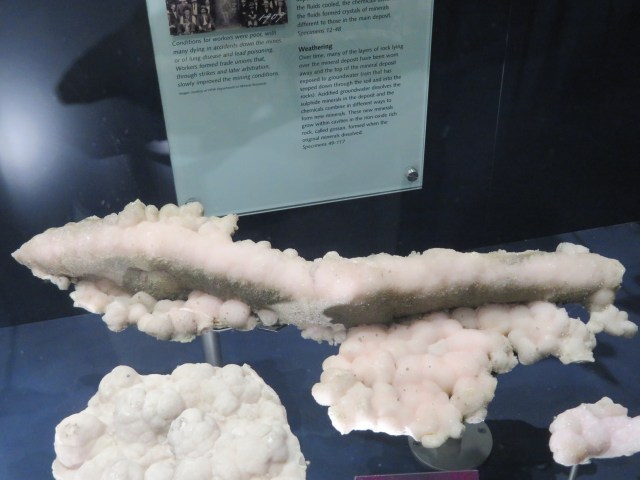

Barite:

It might be hard to see in the photo, but it looked shiny and almost sticky, like resin or something. This particular specimen was mined in Cumbria during the 1800s.

Dioptase on calcite:

This one looks fake in the sense that it looks like it’s been dyed, but that’s really what they look like. It’s a much darker colour than I’m used to seeing in crystals – I guess there’s nothing preventing them from being dark, but I have this image of crystals being light-coloured and usually semi-transparent. Apparently, that image is wrong.

This is scolecite, and it looks like a toilet brush:

Well, that last one’s crystals are too big for it to be a normal toilet brush, but it still looks like something you’d scrub with.

Sulphur:

I know we’re all used to thinking of sulphur as a powder, but this is what it looks like as a crystal – really weird.

Arsenic:

This is actually pretty rare, because this is a sample of pure arsenic, and it usually gets combined with other elements. Somerville got this one from a German museum.

Copper:

Also, that’s not shaped or worked or anything – it really was discovered the way, with little featherings of metal.

Gold nuggets, as they were found:

Those were all found in Australia.

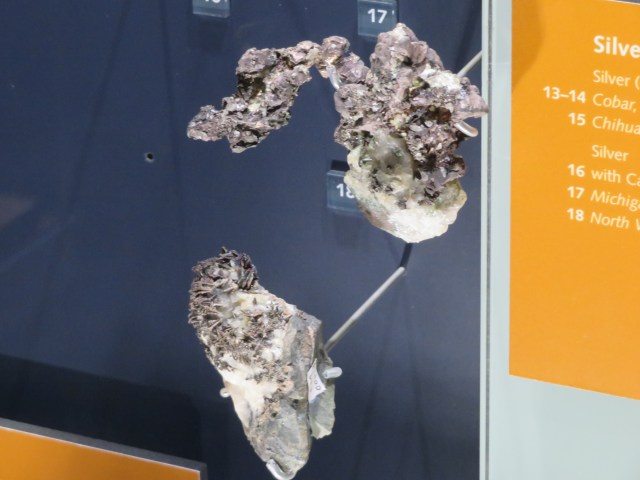

Silver:

Not from Australia – these were found in Mexico.

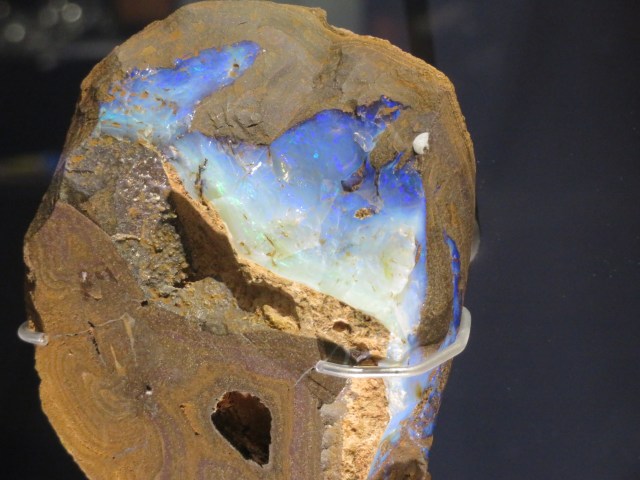

Boulder opal – the Australian classic:

Silicified wood:

Basically, the wood was just converted into silica, but not the kind of silica that gives you opal or agate. Chemistry is complicated.

Silicified fern:

Both the silicified fossils come from Queensland.

Malachite:

It looks like trapped bubbles or something.

Azurite:

Another very dark crystal colour.

Fluorite on quartz:

Yeah, this is the stuff they put in toothpaste, and it makes little cubes when it crystallises.

This is some more amethyst, in what they call an oyster formation:

Yeah, that was pretty spectacular. They didn’t have a good way of giving it scale, but it’s about the size of my head.

Legrandite:

This is a zinc arsenate, known from only a few locations around the world. This particular one is from Mexico.

Pyrite:

Also known as ‘fool’s gold’, because when it’s scattered in rock it’s often yellow and glittery and easily mistaken for gold. Probably not easily mistaken for gold like that, though – I don’t think gold forms those sorts of crystals.

Now onto the fossils! They had a display about the different types of fossils, but since I went over that in Canowindra, I’ll skip the explanation and just show you the pretties!

Ammonite shell, from the USA, between 71-65 million years old:

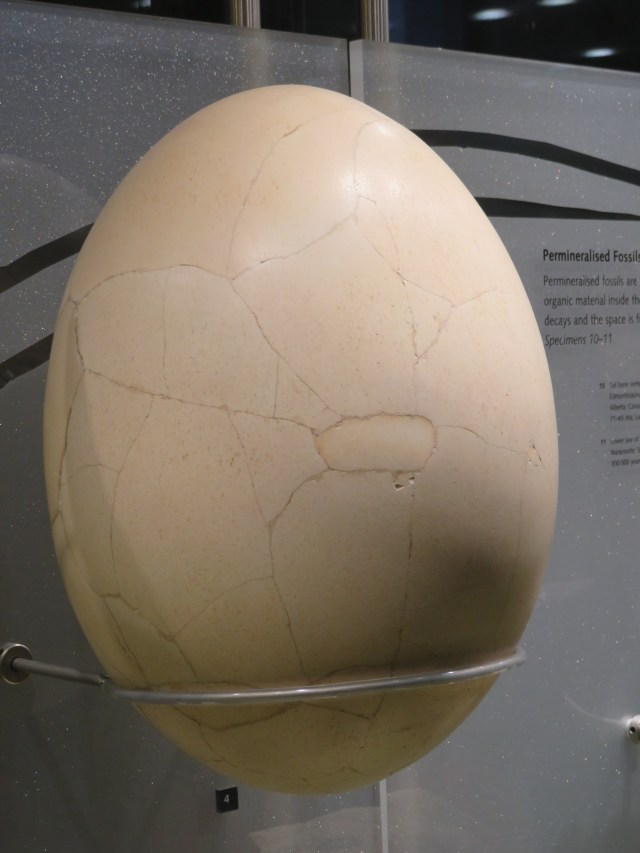

Elephant bird egg from Madagascar, about 10,000 years old:

Which seems pretty young compared to millions of years old, but is still older than all of recorded history.

The tooth of a Great White shark, compared to a Megalodon shark:

Megalodons were, as you might suspect from the tooth, giant sharks that lived from about 24 million years ago to 5 million years ago.

Petrified wood:

Opalised wood:

Pyritised fish:

It’s exactly what it sounds like – a fish turned to pyrite.

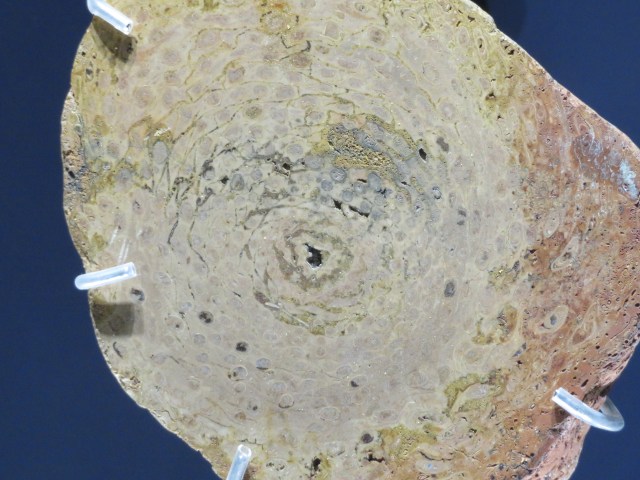

Agatised coral, which doesn’t look like much from the outside:

But on the inside:

And, the one I found most interesting, a petrified crab:

This is between 55 to 35 million years old, and it really shows you how little crabs have changed. That was exactly how it was found, in mudstone, buried by an underwater mudslide millions of years ago. Their theory is that it thought the mudslide was a threat (quite rightly), but responded the way it would to another animal – raising its pincers and opening its mouth in an attempt to scare it away.

Well, we can see how that went.

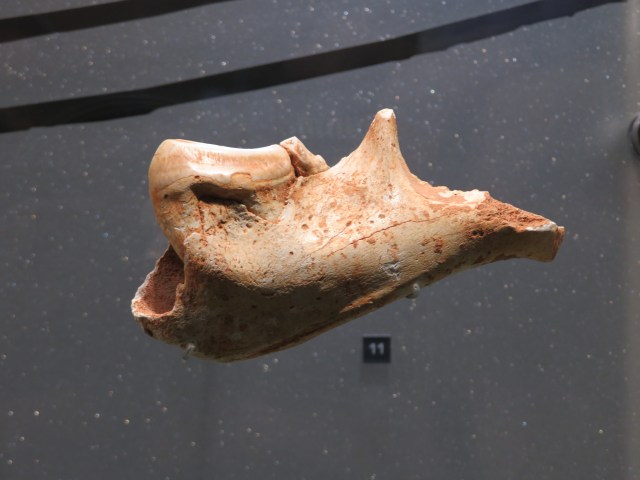

Lower jaw of a marsupial lion, 300 000 years old:

Tail vertebrae of the dinosaur Edmontosaurus, 71-65 million years old:

Carbonised seed fern, from the Triassic:

Carbonised fern, from the Permian:

Carbonised club moss, from the late Devonian:

In the Devonian, they had gigantic mosses that grew like trees. It’s weird to think about.

Fish skeleton in coal, from the Eocene:

A bunch of recrystallised fossils from the Devonian:

I took some close-ups of the wilder ones:

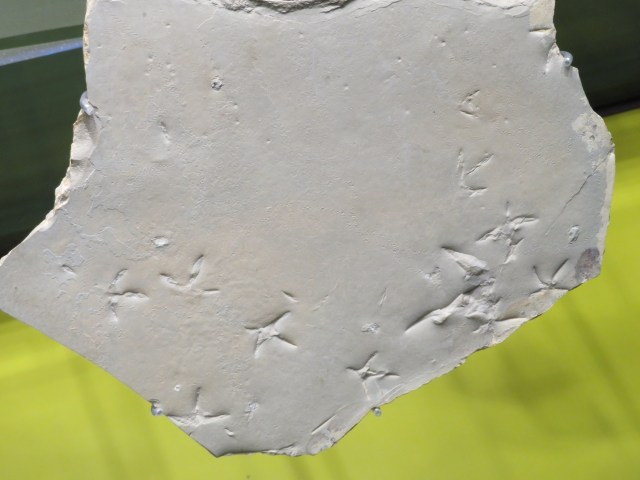

Bird tracks from the Eocene:

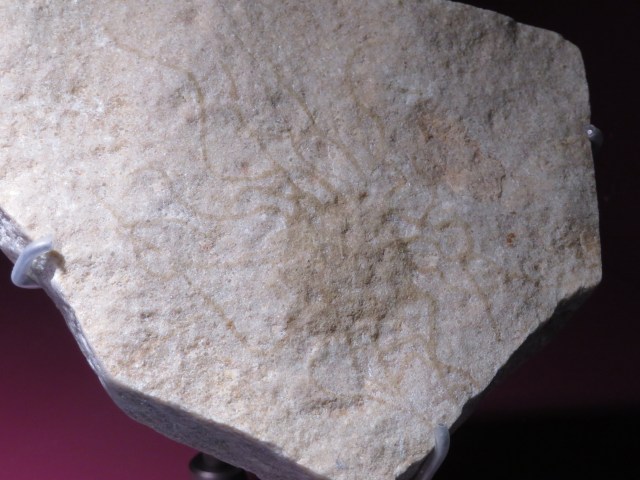

Trilobite tracks:

Worm burrows:

Opalised shells:

Trilobite shell mould, from the Devonian:

Agatised tree stem, from the Eocene:

And now you know what agatised means, so you know why the underside is so smooth and shiny!

Beetles preserved in tar, from the Pleistocene:

There’ll be stuff preserved in amber later as well!

Another fossil of a stromatolite, because I find them fascinating:

I know you guys are probably bored of these, but…first evidence of life on earth! Life that’s still around today, if your mind wasn’t blown enough. I’ll never be over that, never.

In the history of life on our planet, we have about 2 billion years of single-celled lifeforms, because multi-cellular life was difficult to get going, and we still don’t know exactly how they made that jump.

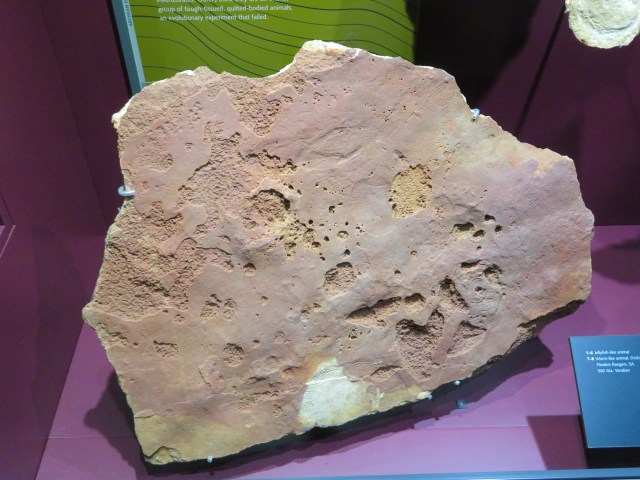

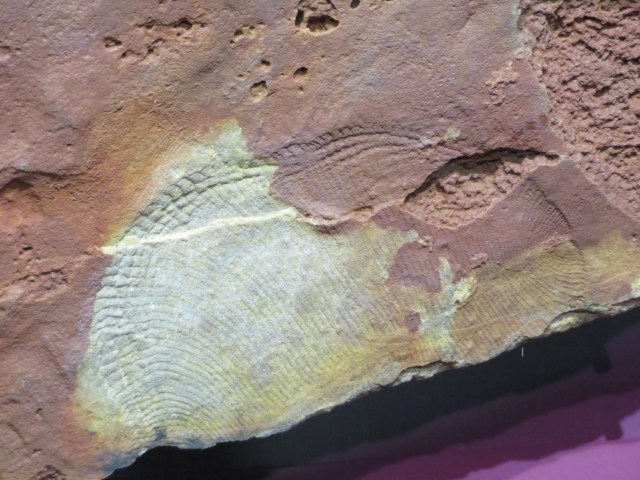

Have some Ediacaran fossils – the earliest evidence of multi-cellular life:

And some close-ups:

There’s not much in the way of descriptions, because we really don’t know much about these critters. We don’t know if they’re the ancestors of the invertebrates, or if they’re a dead-end of evolution, simply because we have so little of them and they’re so different to anything we see after them. So, after years and years of study and comparison, the best we’ve got is a ‘maybe’.

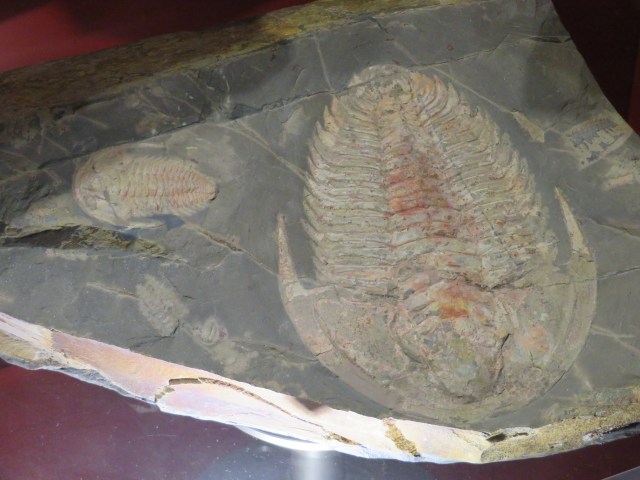

Now, for some trilobites! There were a whole bunch of different species in different sizes, and some of them look pretty wacky:

Other fossils:

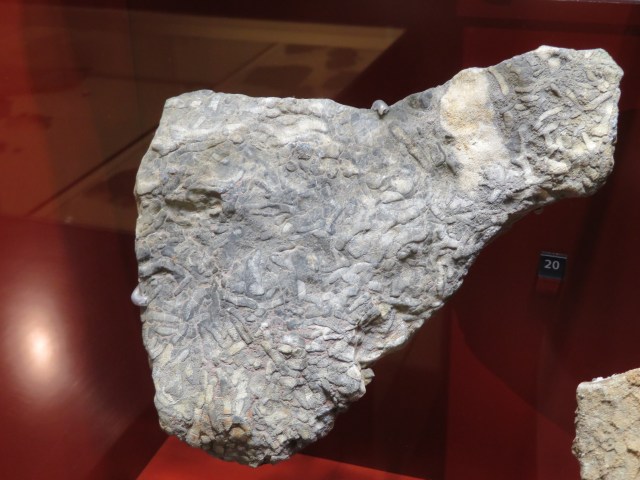

These next fossils are remnants of an enormous coral reef that stretched from Queensland down to Tasmania during the Ordovician and Silurian periods. The coral might look like the ones we have today, but they’re all from extinct lineages:

Sea scorpions from the Devonian:

In spite of the appearance, this is not actually snake skin:

These are more fossils of giant club moss, the ‘trees’ before trees actually existed.

Ferns:

The more you see of the fossil record, the more you realise ferns have been around for a very long time.

This is another notable event in evolution – the leaves of a seed-producing plant:

An amphibian larva:

The equivalent of a tadpole to the amphibians of the day.

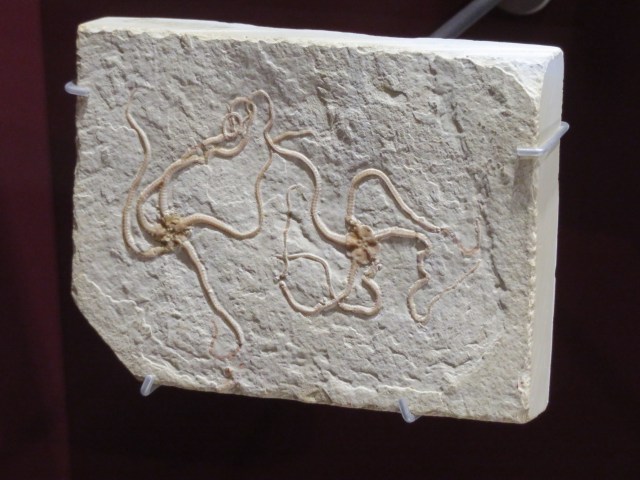

Now we’re into the time of the dinosaurs! This is another beautiful crinoid fossil:

Yeah, it looks like the tentacles of an octopus, but it’s actually more closely related to starfish.

Shells of gastropods (think sea snails, or something like it), very well preserved:

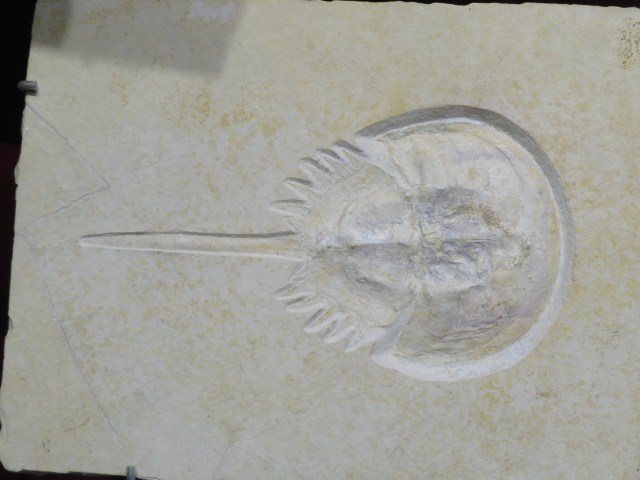

A horseshoe crab:

And guess what? These things are still around today, 450 million years later. In spite of the name, they’re not actually crustaceans – they’re more closely related to spiders (no, I’m not joking). Evolution is weird.

Sea stars:

This one is surely familiar:

Yes, that’s a crayfish. And this one is an unspecified lobster of some kind:

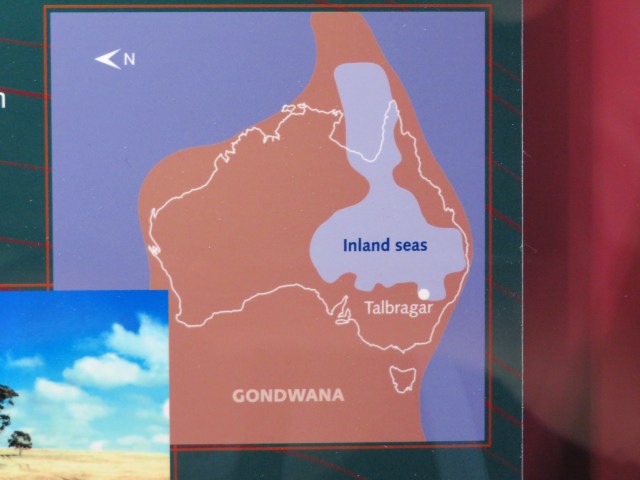

Now, during the Jurassic period, there were a lot of freshwater lakes in Australia, and an inland sea:

From this, we get a lot of fish skeletons:

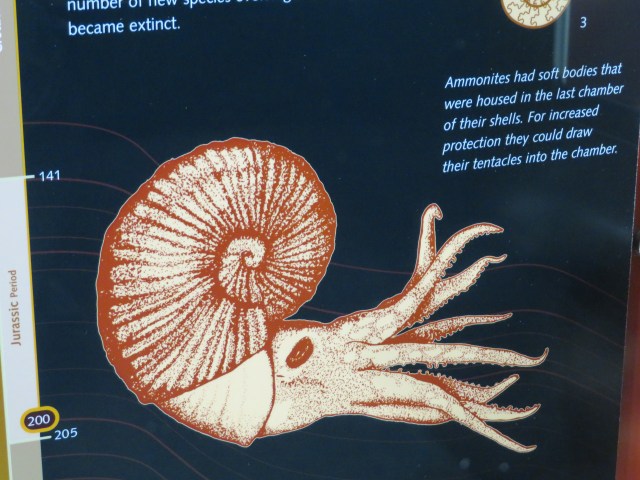

Now for some ammonites! These guys came from the Devonian, but really came into their own during the Jurassic and Cretaceous. Then, at the height of their diversity, they went extinct. This is what they looked like:

When you see the stereotypical fossil with a spiral shell pattern, it’s usually an ammonite – these creatures fossilised very well:

As you can see from the shiny, that one is partially opalised. Here’s some more of them:

Now have some fossil insects:

It’s weird to see how little insects have changed. I mean, those ones up there are very recognisable as a moth, a beetle and a spider.

The tooth and scapula of an Allosaurus:

Close-up of the tooth:

This is an Albertosaurus, basically T-Rex’s smaller, skinnier cousin:

Just a small reminder this is still one dude’s private collection. Yep, even that cast of the skeleton there. But wait, it gets better – this is Thescelosaurus, a small herbivore:

And the crown jewel – Tyrannosaurus rex:

This is the only private collection in the world with a cast of a complete T-Rex skeleton. It was purchased in America, and when the Australian Museum learned of it, they asked to display it, so it went there for a few years before finally arriving here.

No wonder they gave Warren Somerville an honorary Professorship.

That photo doesn’t really show the scale of this enormous thing, so have a picture of me beside the leg:

Yeah, I don’t even make it to the knee. And it’s even more mind-boggling to think that this wasn’t the biggest dinosaur around, and that even the biggest dinosaur ever wasn’t the biggest animal ever. That honour goes to the blue whale of our time, whose sheer vast proportions are best grasped by the phrase ‘its tongue is the size of an elephant’.

Now for some more fossils! This is the lower jaw of Edmontosaurus (a small herbivore):

Cast of a Velociraptor skull:

Preserved eggs:

Eggs in nests:

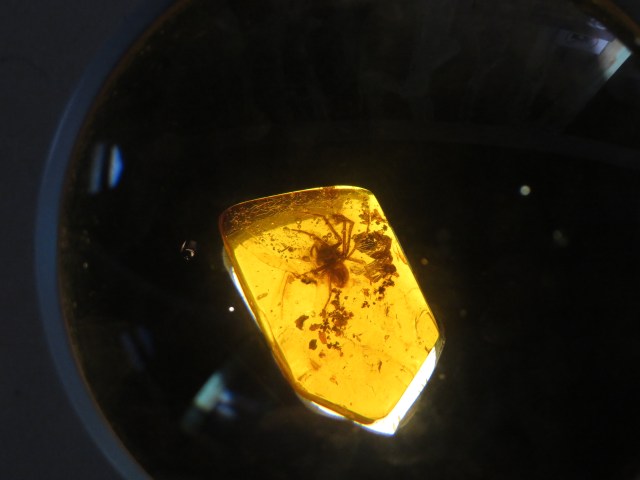

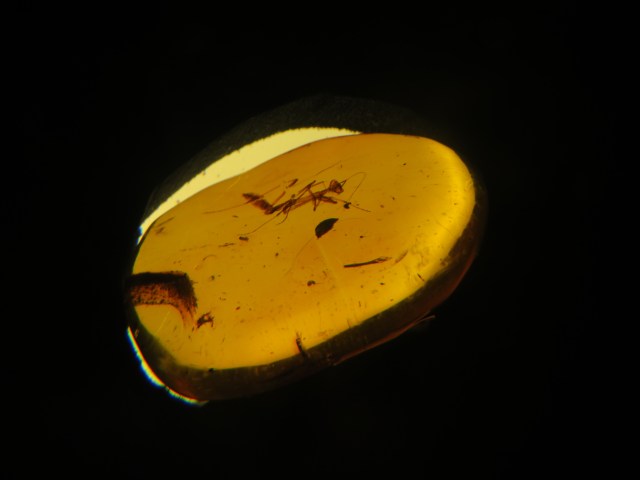

They also had an amazing collection of amber fossils – check out the spider:

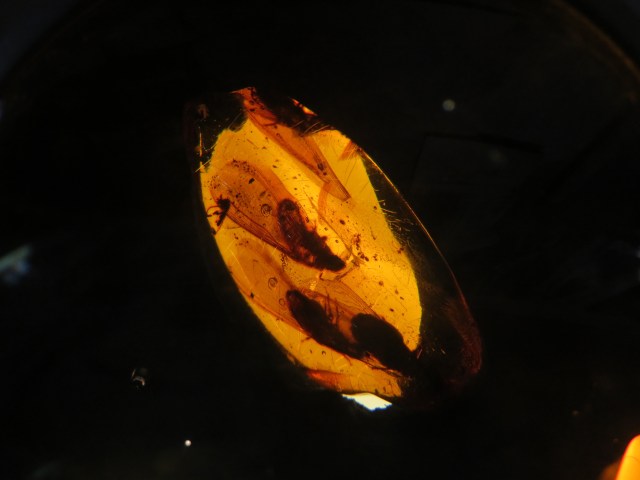

A very rare example of a non-insect preserved in amber, this tiny gecko:

Giant termites:

Cockroach:

Praying mantis:

Ticks:

Bear in mind, the youngest of these are five million years old, and most of them are 30-24 million years old. The insects we know are really old, is all I’m saying.

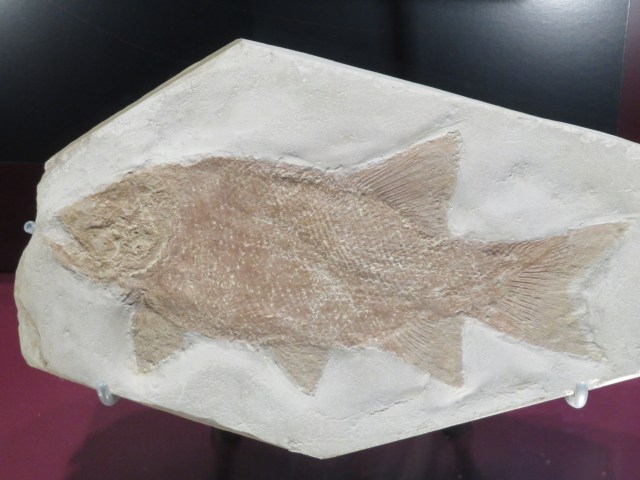

Back to some of the larger fossils – dig these fish:

These are fifty million years old, but they’ve been preserved remarkably well. I took a close-up:

You can see tiny details of their skulls, and even little spines along their backs and bellies.

A rather recognisable leaf:

More fish:

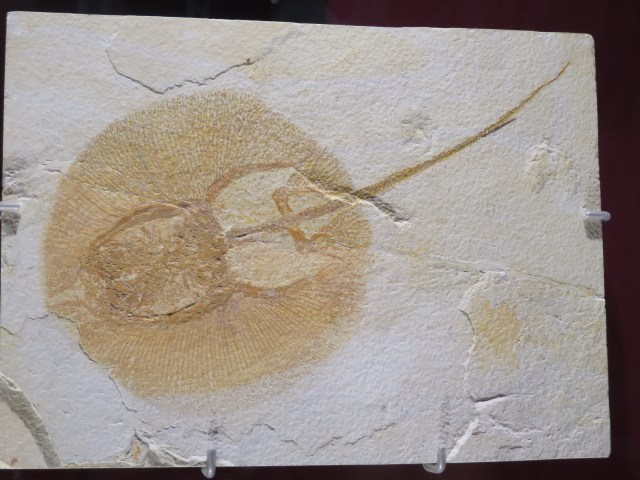

It’s probably just a trick of the light, but the first one actually looks like it’s scowling. Now this outline might look vaguely familiar:

It’s a freshwater stingray! Now we come to some mammalian fossils – a skull of one of the first feline species:

One of the first horses:

This was about the size of medium dog’s skull. Which makes a neat segue into the early canine:

Which was about the size of a rat.

This is an early deer, just a bit smaller than the horse:

Early pig, about the same size as the horse skull:

Most of the early mammals were kind of small. Then they evolved:

This is the skull of a Smilodon, also known as the sabre-toothed cat (and that scientific name is proof biologists have a sense of humour). It’s also only distantly related to modern cats, though. As you may know, Smilodons weren’t small, and may have been the largest known felines.

This is the paw of a cave bear (yes, like the book):

This was even bigger than the Smilodon – about the size of the grizzly bears we have today. Fun fact: almost ninety percent of cave bear skeletons we have today are male, because the female skeletons were assumed to be ‘dwarfs’ and discarded. Though in all fairness, it seems the average weight for a male cave bear was 400-500 kilos, while a female was 225-250 kilos, which is a pretty extreme sexual dimorphism.

This is the tooth of a cave bear:

It’s about as long as a finger.

Then I found the Australian mammals – this is the skull of a rat kangaroo:

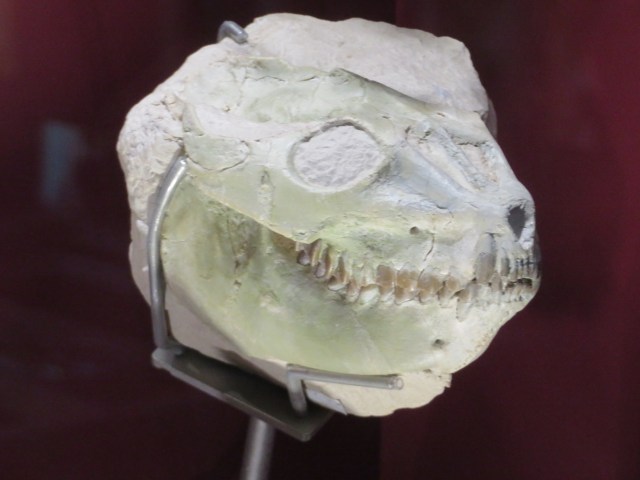

And this is the skull of a Diprotodon:

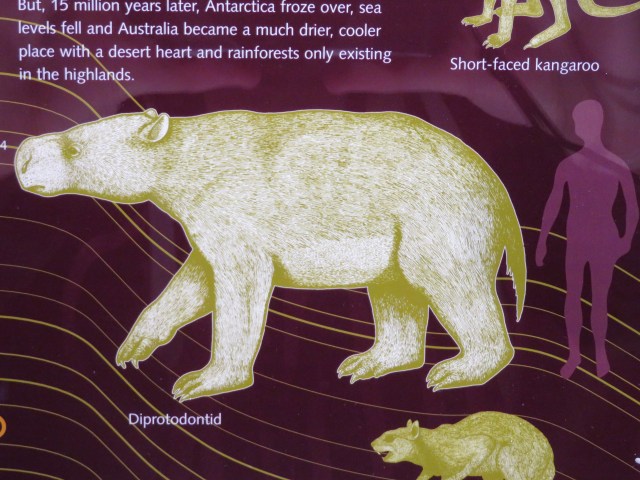

Diprotodons were the largest known marsupials, and were even larger than the cave bear. This is their size compared to a human:

Another lobster fossil:

I just love how it’s stuck in the rock, with only its claws and tail showing.

A crab:

Not quite as good as the petrified crab, but still pretty cool.

They also had a display devoted to opalised fossils – this is the inland sea again:

Those towns are known for their opal deposits, remnants of the sea that existed over a hundred million years ago.

They had a large slab that didn’t look like much:

Until I realised it was full of opalised shells:

These are a bit of a sad story:

These are the shattered bones of two opalised plesiosaurs, found in the opal fields of South Australia and smashed into pieces by miners looking for jewellery-quality opal. You can see the remaining bones are shiny, but not quite good enough to be set in expensive jewellery:

What is left makes up about 15% of a 7m long specimen, and 25% of a 3m long specimen. But this is a work in progress – though it may seem like jumbled pieces to us, the museum is actually working on piecing together the bones to form partial skeletons, which will then be hung up on the wall.

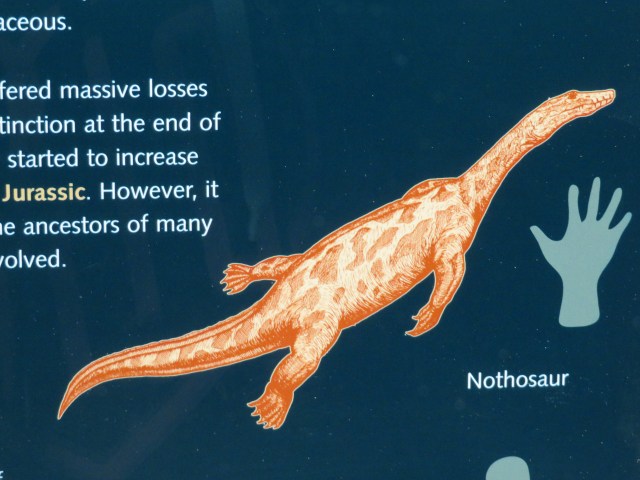

They also had a display on these marine reptiles, complete with comparative sizes. First up, the Nothosaur:

Pretty small, would make a very exciting aquarium pet.

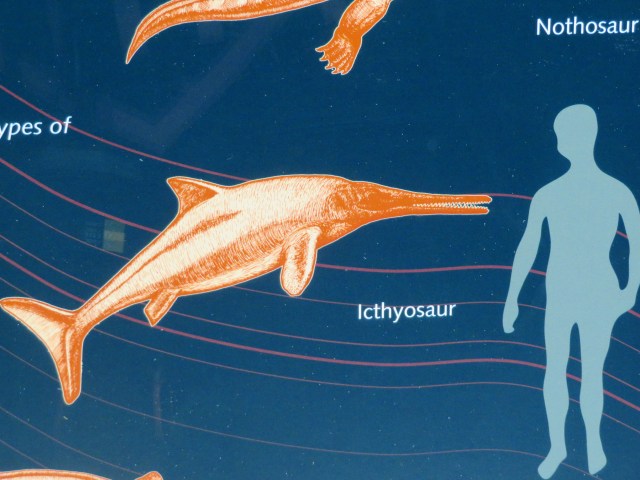

Icthyosaur:

Its paddle-like limb:

Looks scary, but not nearly as scary as the next one.

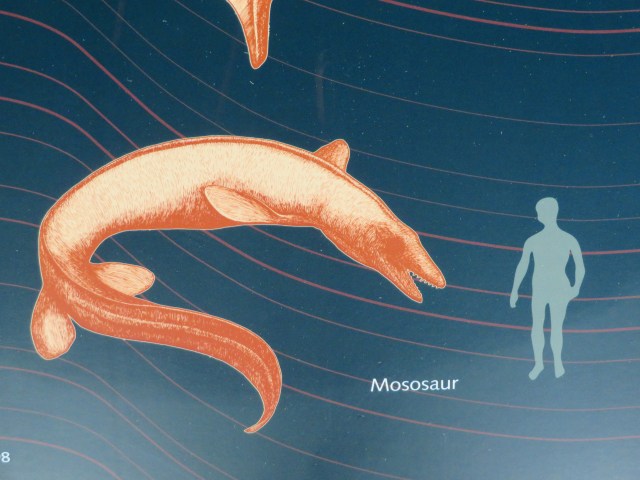

Mososaur:

One of its teeth:

This was the dangerous one – see that shark-like mouth? Could definitely eat something human-sized, though these were long extinct by the time humans were around.

More fishy fossils:

The last one doesn’t look friendly, does it? Check out this pair of fish skulls unearthed in Queensland:

This one is a species that hasn’t been named yet:

This little gallery was on the second floor, which put me level with the T-rex skull:

It’s pretty intimidating, isn’t it?

I also had a nice chat with a volunteer there, a middle-aged man who was ready to give me a general speech about how fossils are formed and how rare they are, until I revealed I knew quite a bit about fossils already. So the both of us geeked out together at how incredible this sort of thing is for quite a while, discussing how the various periods relate to each other, the mysterious Ediacaran period, the marine expansion in the Devonian and other interesting (to us) stuff, until he remembered a job he needed to do and had to leave. Before we said goodbye though, he told me, ‘if you ever want a volunteer job here, you’ve got it’.

So, if I actually do get a job here in Orange, that might be nice to do on the weekend or something. Fossils are just so fascinating, because they’re basically time travel, ‘here, this is something that existed millions of years ago, have a look at it’. And that’s not even getting into how amazing it is that all this happened right where we are now. As the Land Before Time put it; “Once, upon this same Earth, beneath this same sun…”

Gives you goosebumps to think about, doesn’t it?

The museum also had a Lego display (because why not), of The Mount, a nearby racetrack, so prepare for a lot of photos:

You can tell it’s an Australian race, because of the kangaroo on the track. And I admit I took that photo of the Lego caravan purely for sentimental reasons.

But I wasn’t quite finished. Bathurst also boasts the Big Gold Panner:

So I had to get a picture with him:

He looks either stoned or drunk, but Deadwood has taught me that’s probably very authentic to the old gold panners. Then I headed back to Turtle Shell.

I’m actually typing this up on Friday, though, while my laundry is hanging on the clotheslines. It was very cold tonight, which made my shower an interesting experience – the temperature was just ‘warm’, but it was producing so much steam in the cold bathroom that it looked like a fog machine was going. My feet were just blurry outlines through it.

Loving the blog! I’ll be sure and let you know if I ever get to use “vugh” in a conversation xXx

LikeLike

It’s pretty hilarious, isn’t it? English is so weird.

LikeLike

Fantastic, as always. Love your work. If you go back to Bathurst, drive the race circuit – stunning views from the top and corners that are scary at 430kph, let alone race speeds.

See you soon

LikeLike

Good idea – I’ll make a note of it. Bathurst isn’t exactly far away.

LikeLike

Stibnite! And the petrified crab. And the fossilized crinoid, and the … Great stuff. Generous man Mr Somerville – well worth a professorship

LikeLike

Sometimes that ‘honourary’ stuff doesn’t feel earned – this was definitely earned! I spent a very long time staring at that crab…

LikeLike

Love the fossils! I, too, get goosebumps from that quote- one of my faves. It’s an amazing concept. That crab is definitely on it’s own, but ALL of it’s very good stuff.

LikeLike

I thought of you with that quote! And I did spend a very long time staring at the crab…

LikeLike