The balloon challenge comes later in the day – my first stop was the Age of Fishes Museum.

As the name suggests, it’s largely based around the Devonian period – the titular age of fishes – but it also had some interesting signs based around the various evolutionary periods that I found interesting. And you guys might find boring, but this is my blog, so suck it up (or just scroll past it, whatever, I won’t tell you how to live your life).

The first one was about the Proterozoic Era, which lasted from 1000 to 542 million years ago, and literally means ‘first life’. The Ediacaran period is the last period of this era, and is named after Ediacara in South Australia, where the first fossils from this period were found. At the time, the earth look like this:

The fossils:

There aren’t many of these fossils because the animals were soft-bodied, which means they don’t fossilise easily. They also bear little resemblance to any other life forms, even the ones in the Cambrian, which came just after them, so no one really has any idea how they fit into the evolutionary tree. Are these the ancestors of the Cambrian animals, or did they all go extinct before the Cambrian? We may never know.

You’re probably thinking that at least some of them have to be ancestors of the Cambrian life, but not so – it’s estimated that only about 1% of extinct animals are in the fossil record, so it’s entirely possible that the ancestors of the Cambrian animals weren’t preserved. It sounds crazy, but actually makes sense when you think about it; it takes a lot of luck to make a fossil. First, the animal has to die, and it has to die in the right way, in the right place. The body has to be undisturbed, so sediment can form around it to become rock, and then the rock has to stay intact, not sink back into the mantle or be destroyed in earthquakes or the like. And then, even if all that happens perfectly, it has to be discovered, and recognised as a fossil. There are so many stories of amazing discoveries made by sheer chance, when someone thought what they’d found was interesting or unusual enough to go to the trouble of contacting someone better informed, that there must be an equal number of discoveries missed because no one thought that weird thing was worth bothering about, so they broke it up for gravel or tossed it in a landfill.

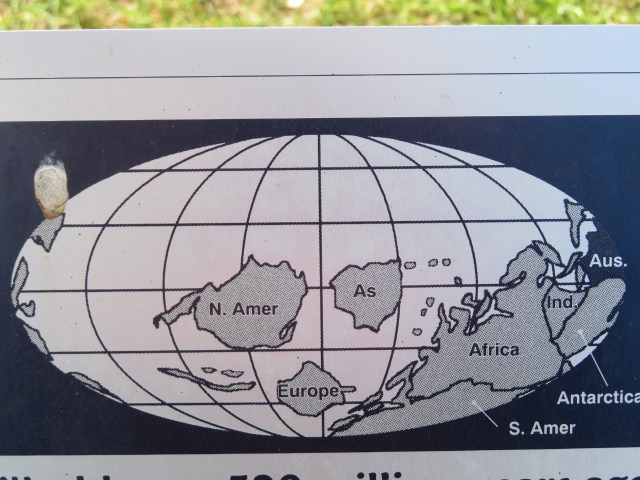

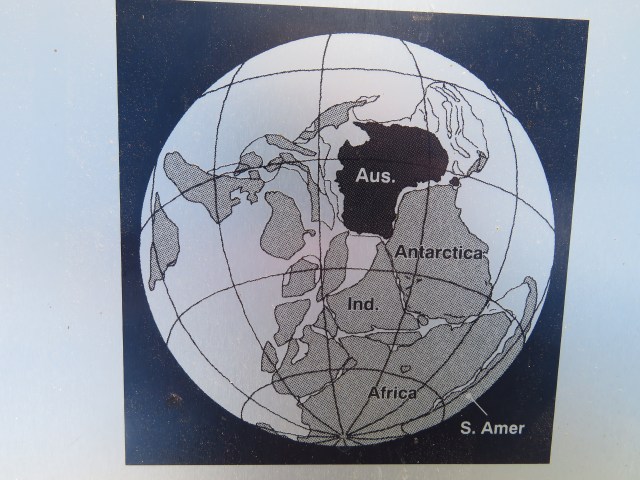

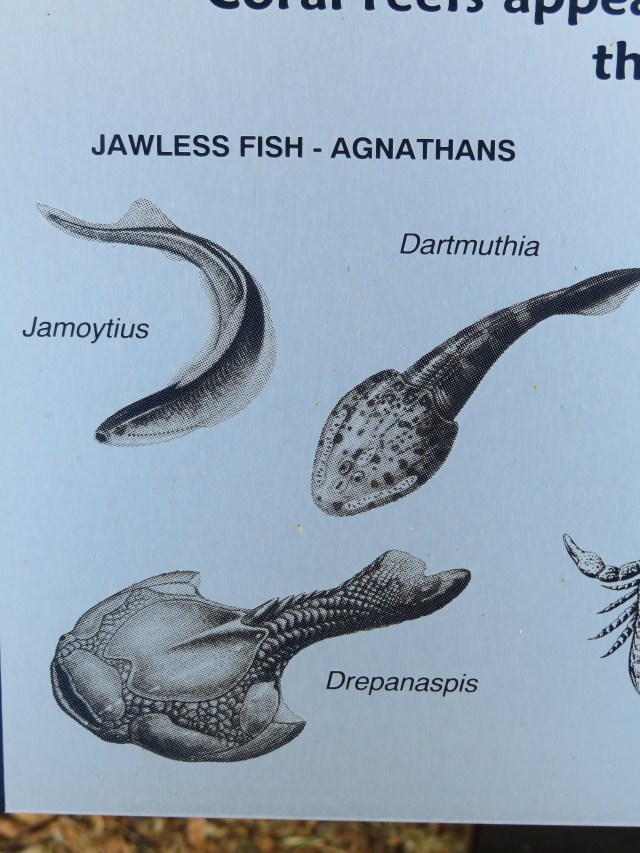

Anyway, onto the next one – the Palaeozoic era (ancient life), and the Cambrian period, which was from 542 to 488 million years ago, when the earth looked like this:

Most of the land masses were grouped together in a supercontinent called Gondwana. You can just see Australia on the border, on the equator. Most of the northern hemisphere was one giant ocean.

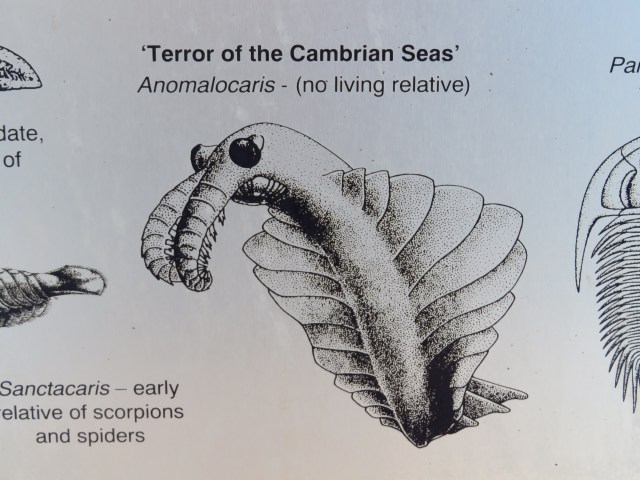

This was when a lot of animals developed mineralised skeletons, so they fossilised more easily. We know that most major animal groups appeared during the diversification of this period, and the phenomenon is called the Cambrian Explosion. Most fossil sites have only preserved the hard parts of the skeletons, but some sites are famous for preserving soft tissue detail as well – in Canada, China, Greenland, and Australia. These are illustrations of the kind of animals found in the Cambrian:

As you can see, they look pretty weird and pretty far from anything we have today.

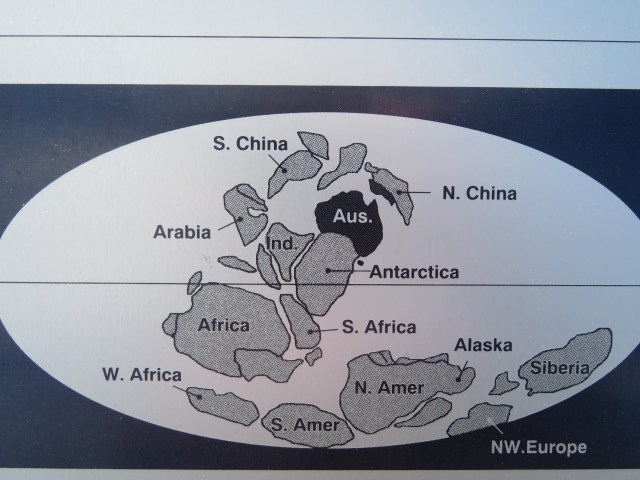

Then came the Ordovician period, from 488 to 444 million years ago. Australia was still part of Gondwana, but they gave a different perspective of it:

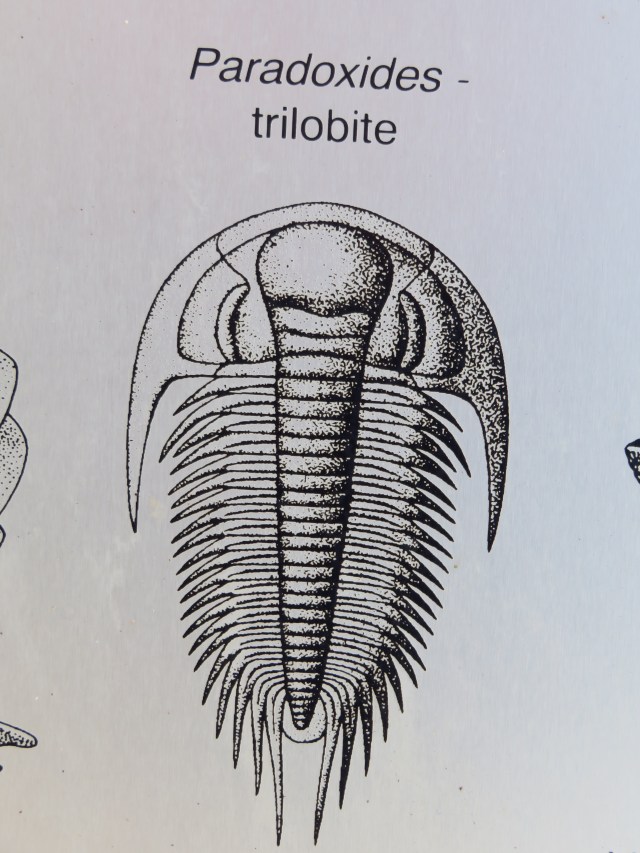

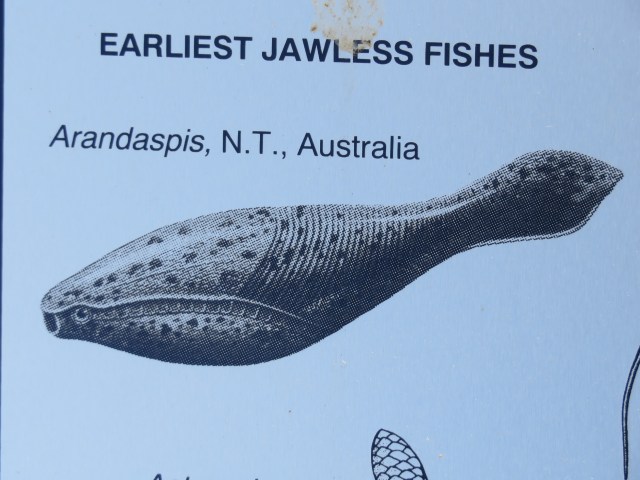

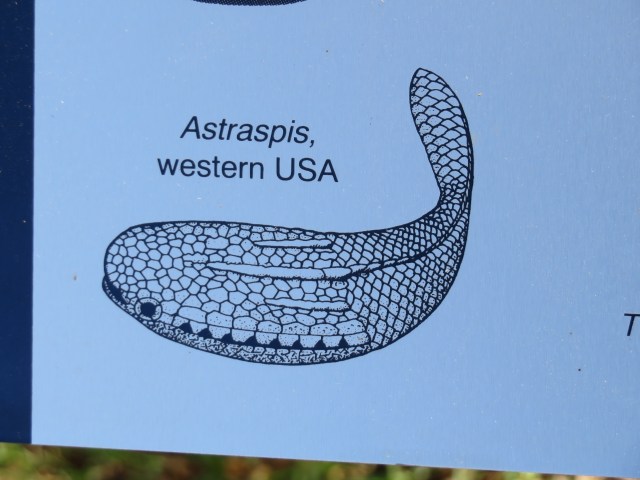

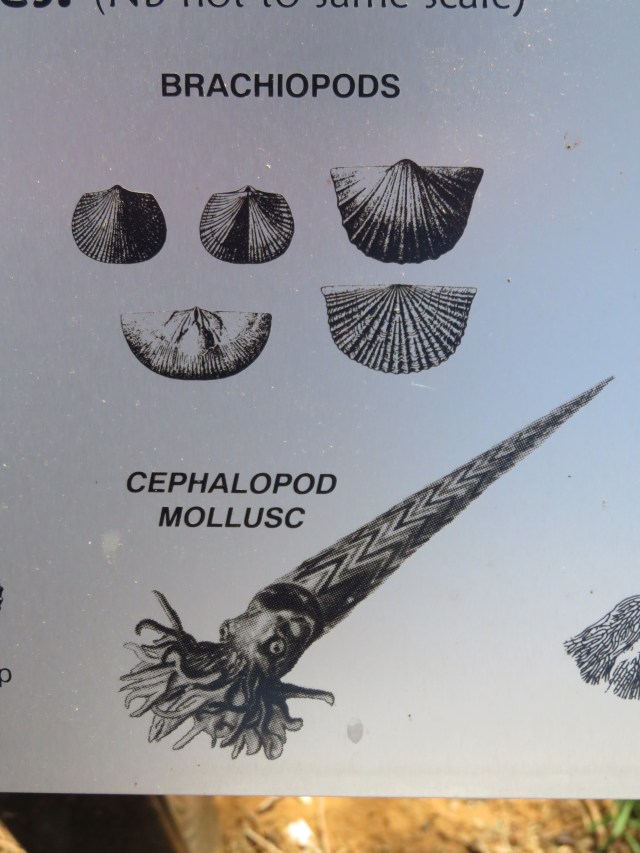

Yeah, that’s Africa over the South Pole – pretty weird to think about, huh? Most of it was covered in ice, but there was still a lot of life in shallow seas, including the first fishes:

The brachiopods are familiar, and the fish are starting to look like modern aquatic animals (well, more like tadpoles than fish, but still). The oldest fish fossils are found in America and Australia – Australia having really old and really rare fossils is a common theme, as I’m sure you’ve noticed.

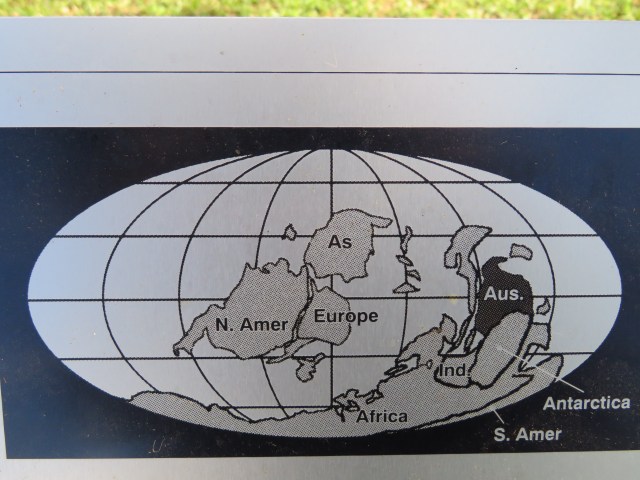

The Silurian period was next, from 444 to 416 million years ago, and the earth looked like this:

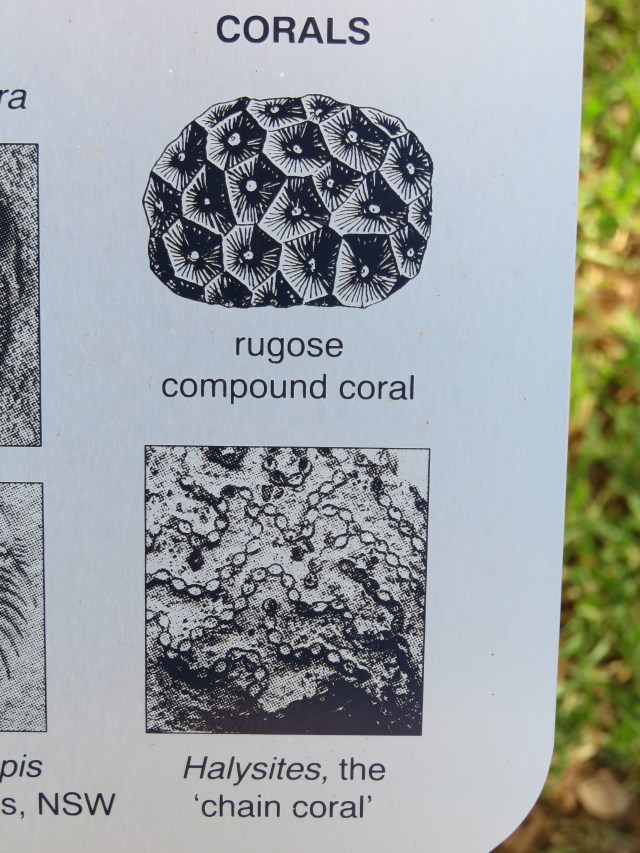

Gondwana has shifted a bit, and the land masses to the north formed the ‘Old Red Sandstone Continent’. A lot of the ice had melted, so the sea levels had risen and marine life blossomed in lakes and rivers. The first coral reefs appeared in this period:

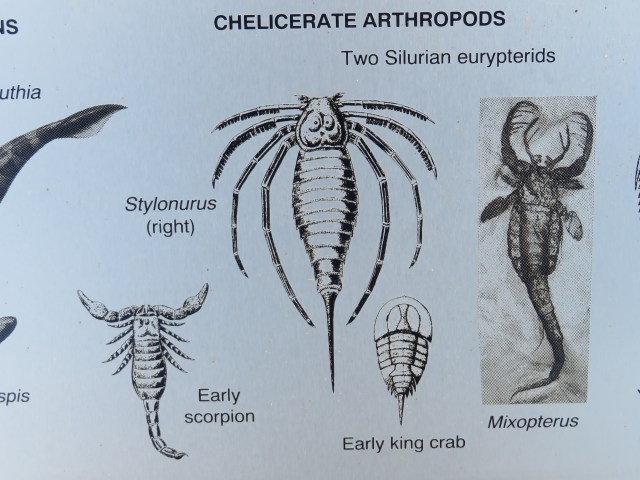

Along with the armoured fishes – fish with armour plating to protect them from predators (usually the early scorpions and king crabs):

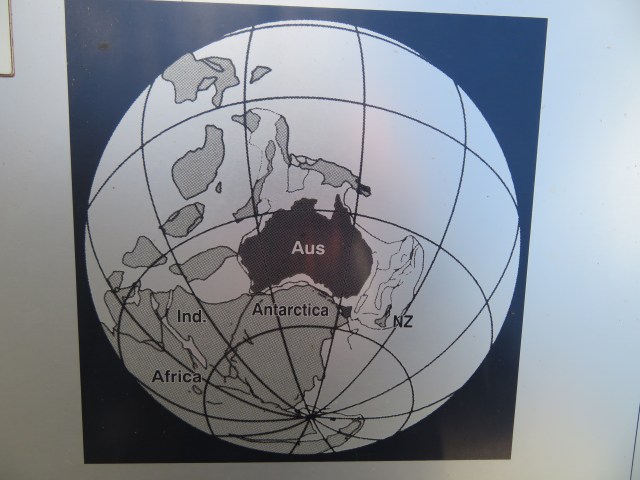

Finally, we’ve reached the Devonian period, which lasted from 416 to 359 million years ago. This is the titular ‘Age of Fishes’, and this was where Australia was:

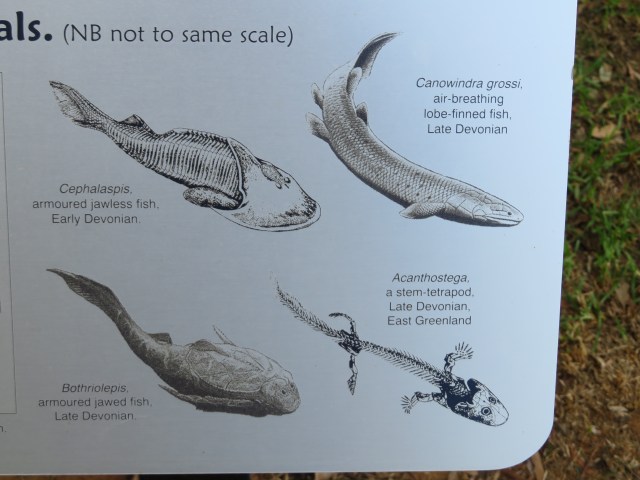

At this point, there was life on the land, but it was pretty limited – mosses, algae, insects, that sort of thing. Jawless fishes were replaced by jawed fishes, and sharks emerged in this era:

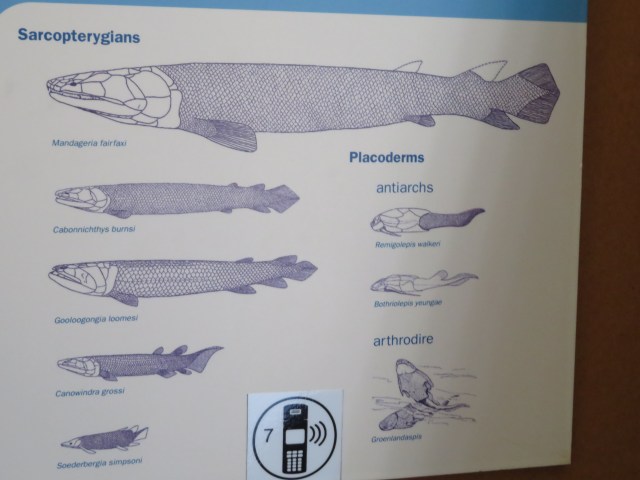

There were two groups of bony fishes – basically, fish with an internal calcium skeleton – the ray-finned (actinopterygians) and the fleshy-finned (sarcopterygians). Actinopterygians is the group most living fish belong to, and sarcopterygians went on to develop lungs and limbs, and became the ancestors of all amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals. Pretty good going, really.

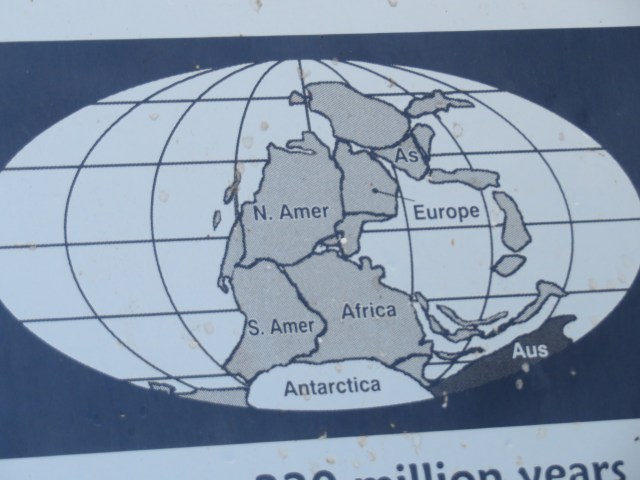

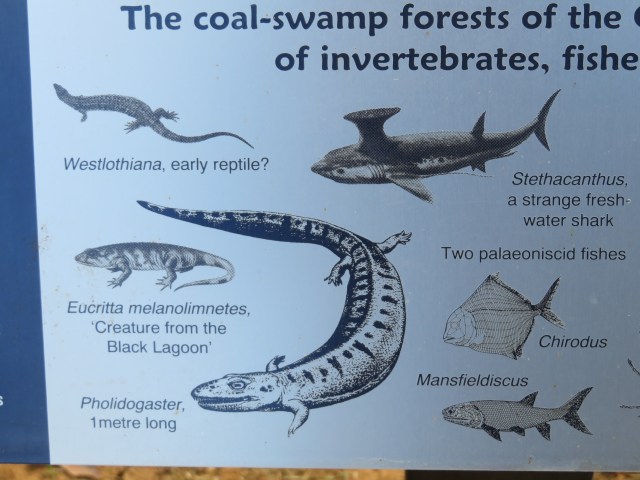

Then came the Carboniferous period, from 359 to 299 million years ago, with this arrangement of the continents:

Still looks ridiculous, and nothing like what we know today.

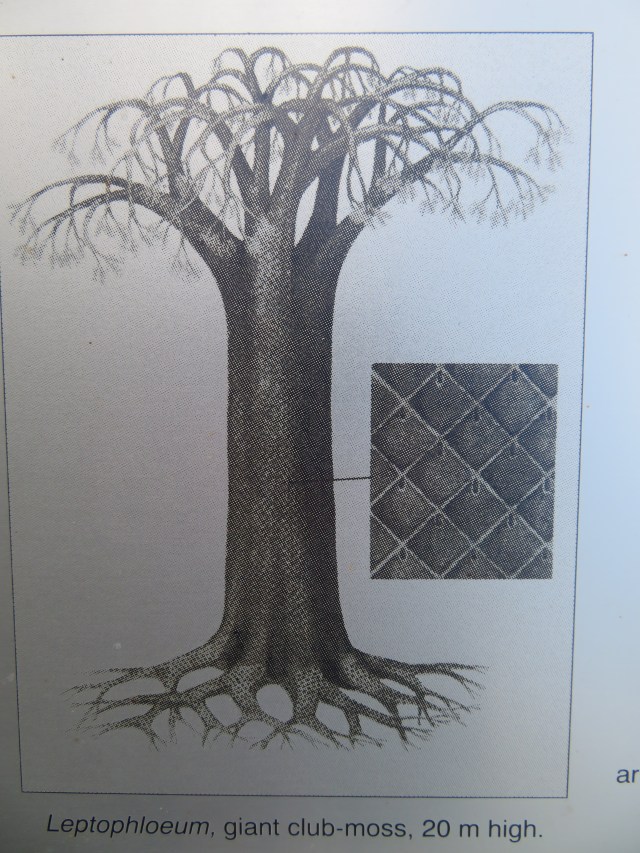

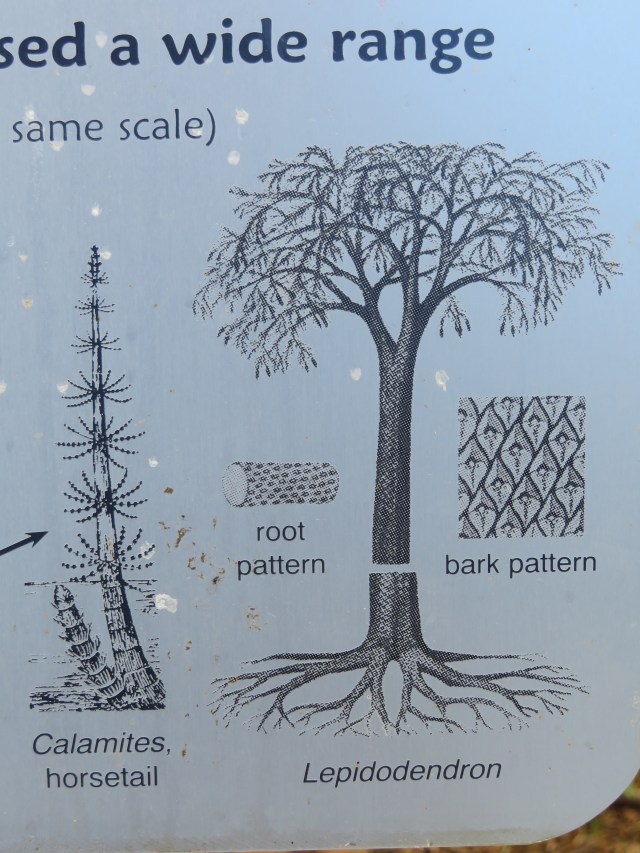

This period is known for leaving huge coal deposits, because plants had developed wood at this point, but nothing that could break down wood had evolved yet, so it stewed in swamps and eventually became coal, oil, etc. rather than being broken down by fungi and the like. This period also had a higher oxygen content in the atmosphere, about 35%, which let insects and arthropods grow to enormous sizes – there were dragonfly-like creatures with 70cm wingspans, and millipede-like animals that were over two metres long. Amphibians were also quite diverse, and while most of them were small, there were giants that lived partially out of water, and grew up to six metres long:

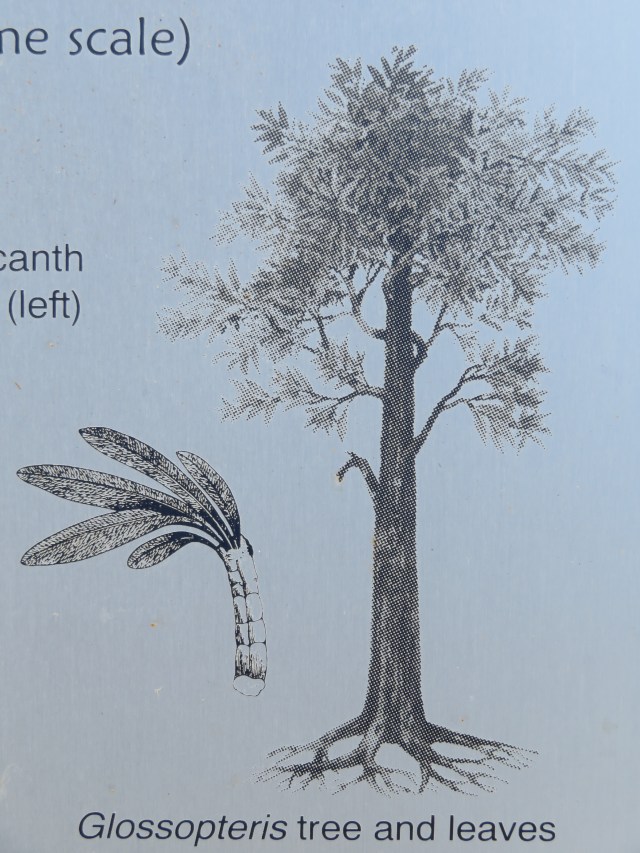

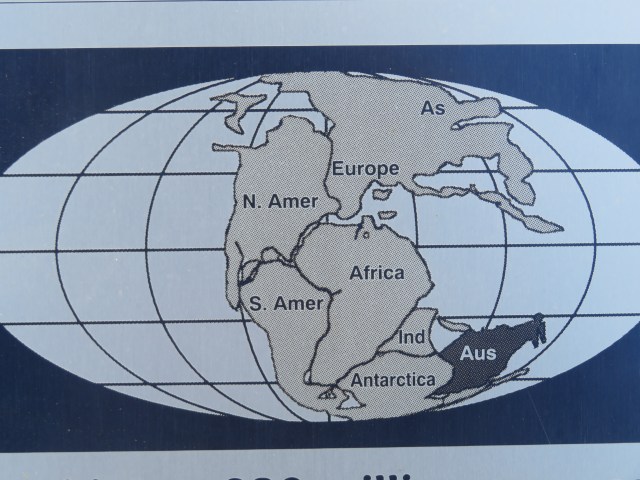

The Permian was next, from 299 to 251 million years ago, when Australia was here:

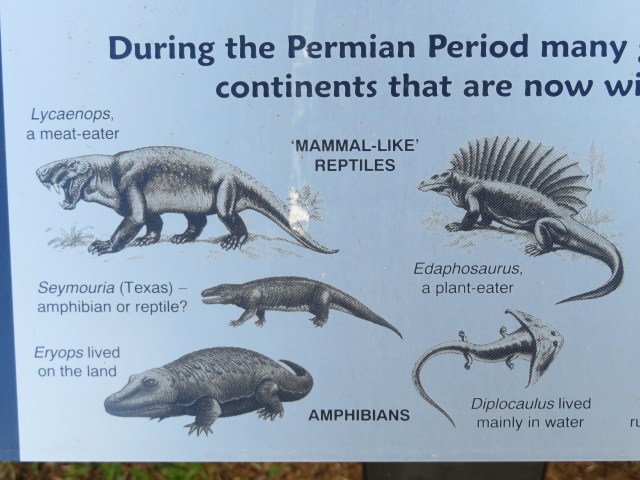

Amphibians and reptiles flourished in this period, and there are plenty of fossils with the features of both, which makes it difficult to classify them. One dominant group of reptiles were the synapsids, many of which walked with their legs tucked under their body, suggesting they could run fast:

It says the ‘last of their line’ in that photo above because the extinction event at the end of the Permian was the most devastating ever – about 90% of all life died, and it was the end for a lot of ancient lineages.

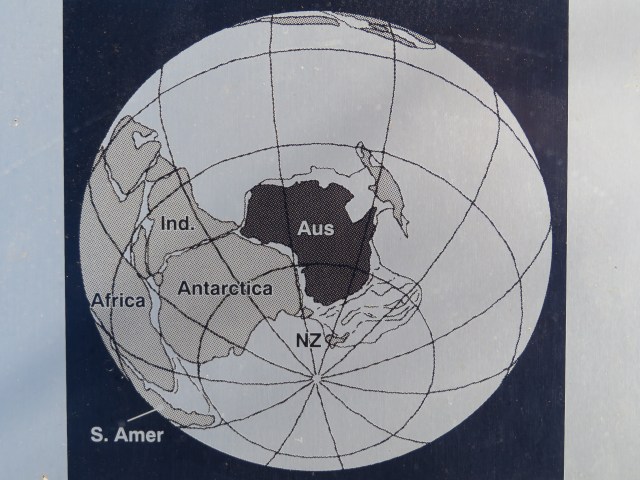

The end of the Permian was the beginning of the Mesozoic era (middle life), and the first period was the Triassic, lasting from 251-200 million years ago. This was the world at the time:

All of the continents were concentrated in one supercontinent called Pangea, which stretched from pole to pole, and drastically affected the circulation of the oceans. If you look closely, you can see a gulf between Europe and Africa, and this would eventually separate the continents.

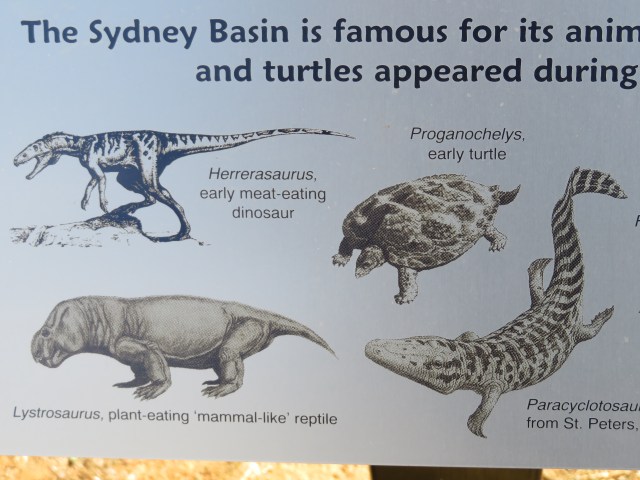

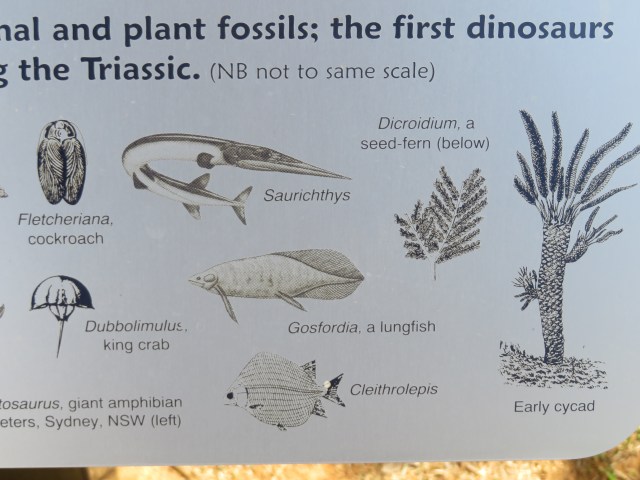

There seemed to be no ice at the poles, and the Triassic climate was probably hot and dry. Lungfishes emerged in this period, and a lot of reptiles returned to the sea to become plesiosaurs and the like. The synapsid reptiles didn’t do so well in this time, and were gradually replaced by archosaurian reptiles (the ancestors of dinosaurs, crocodiles, and birds), but don’t worry – they’ll be back.

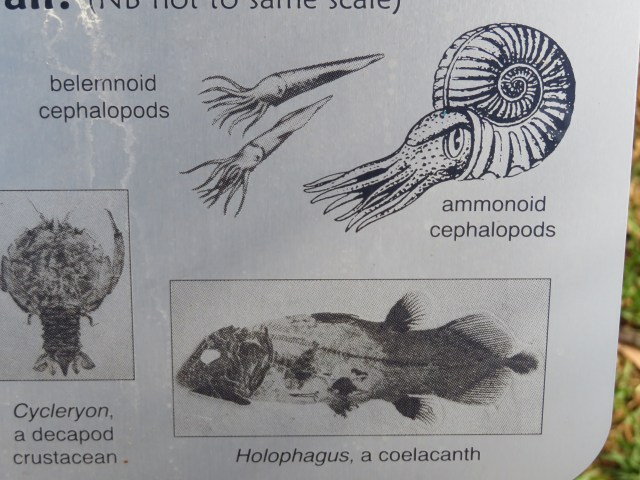

Animals from this period:

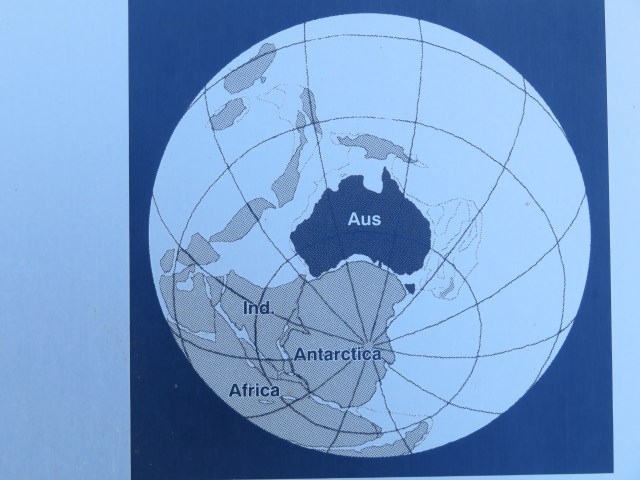

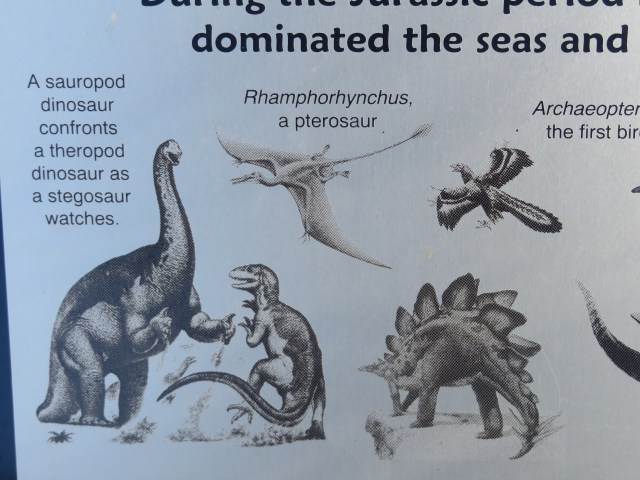

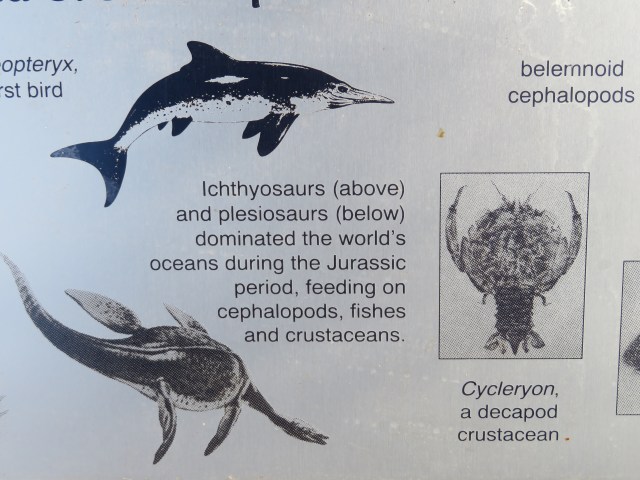

The Jurassic period was next, from 200-146 million years ago, when Australia was here:

At this point, Pangea had broken up into Laurasia in the north and Gondwana in the south. Still no ice-caps, and the climate was very warm.

The archosaurians have become the dinosaurs by now, and the first birds are emerging. The synapsids haven’t made their grand comeback yet, but it’s coming, though at this point, they aren’t reptiles anymore – the synapsids have become the mammals.

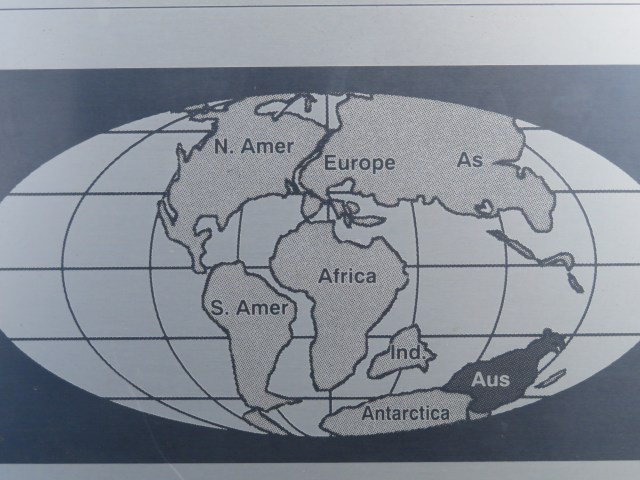

The Cretaceous period is next, from 146-66 million years ago. The world is now much closer to what we know:

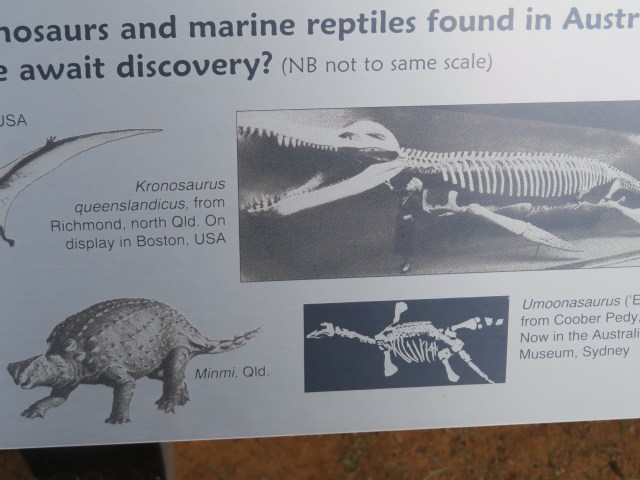

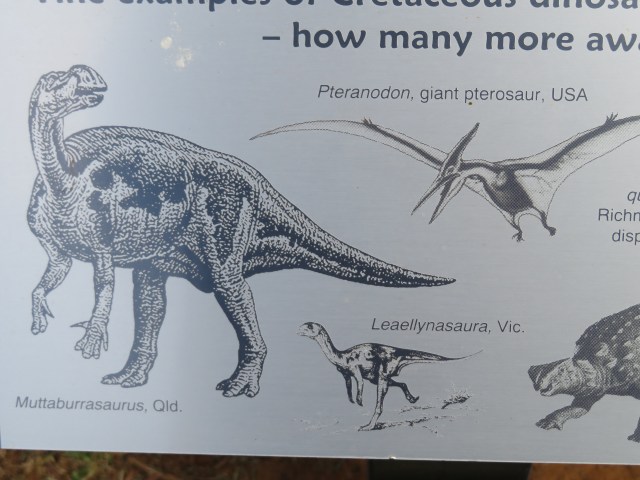

Still not quite there – North and South America have yet to join, Australia is still linked to Antarctica, and India has a long way to go, but it’s recognisable. Dinosaurs still dominate, but this is their last hurrah:

The extinction event that ended the Cretaceous period also ended the dinosaurs – those lineages that had evolved into birds survived, and the sudden depletion of the reptiles meant that mammals quickly diversified to take their place.

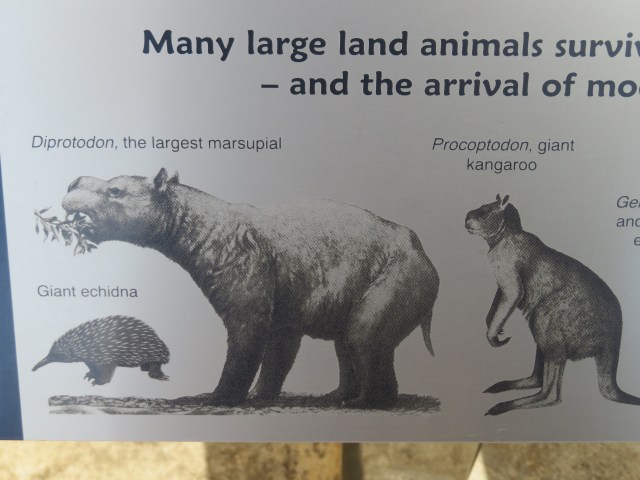

Now we’re in the Cenozoic (new life) era, and I mean that literally because this is the era we’re living in today. The continents are in their familiar arrangement, but there was a period of megafauna before the modern period:

They also had a Wollemi pine in the corner of their little garden:

Which you might remember from my bit about the Coffs Harbour Botanic Gardens as being a living fossil, thought to have gone extinct millions of years ago until some were discovered in a National Park in Australia.

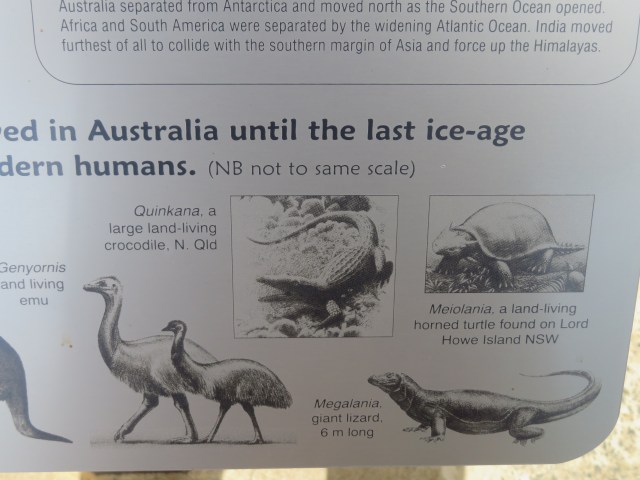

They had a pretty little diagram about the various periods in evolution:

There was a display comparing various types of fossils. Though this one is hard to see, you might be able to make out the shadows of insects trapped in amber:

This is complete preservation, where almost everything remains (though there is some loss of soft tissue). As you can imagine, it’s very rare.

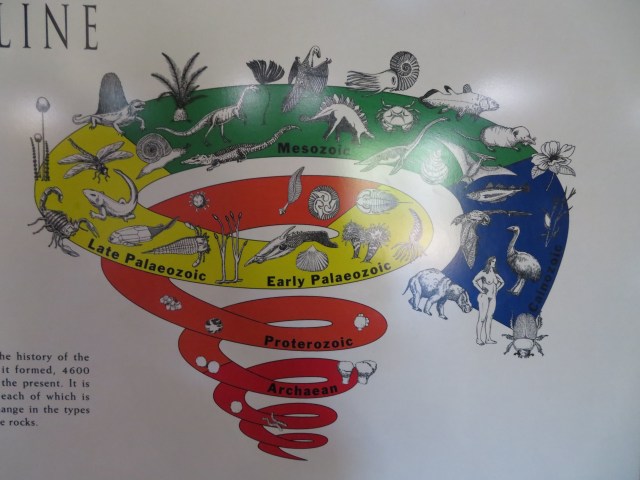

This is partial preservation:

This happens when the plant or animal decays and leaves an impression in the rock. Nothing about the organism itself remains, but the rock retains the impression, and they can be very detailed.

Some fossils preserve only the hard parts of an organism, such as the skeleton, while all the soft tissue is lost, like these fish:

In other fossils, the hard parts remain, but are altered, as their original chemical composition is changed over many years. For example, this is an ammonite fossil where the shell has been replaced by pyrite:

Trace fossils preserve evidence of animal activity, like burrows, nests and footprints:

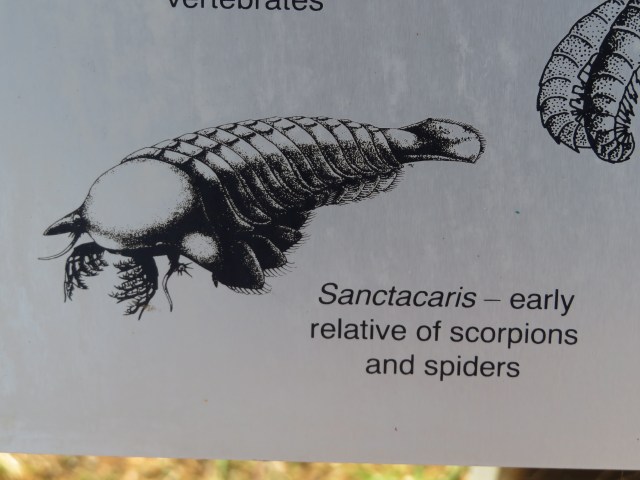

Remember this thing from the Cambrian?

This was one of the first arthropods, but it took a while to be identified, because its mouth piece, body and grasping legs were all discovered separately at first, and were identified as other animals (a jellyfish, a sponge or sea cucumber, and a shrimp, respectively). It was only when a fossil of the whole animal was found that all those parts had to be re-identified as belonging to one animal.

The museum had a fossil of its grasping legs:

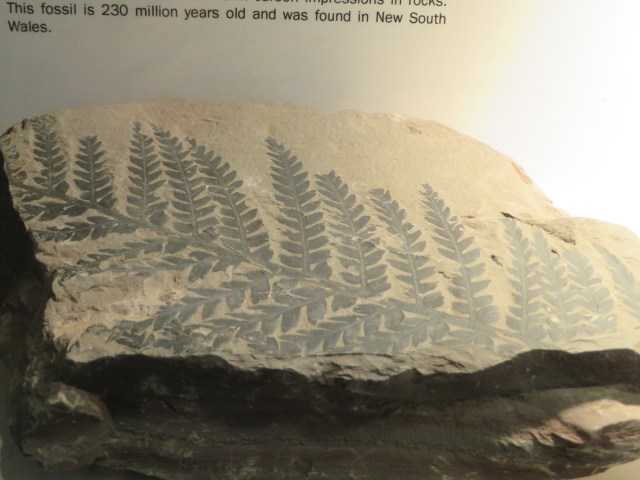

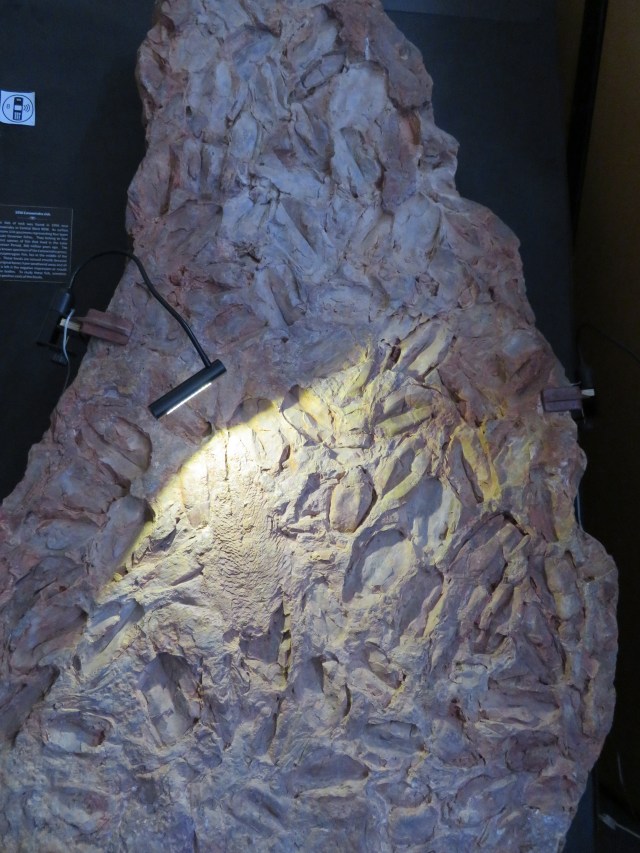

Now, you might be wondering why Canowindra would have a museum largely devoted to the Devonian period. That’s because Canowindra was the site of a famous discovery in 1956, during the construction of a road, when a bulldozer uncovered a large rock with strange markings:

The driver thought it was unusual, and contacted the closest thing Canowindra had to a biology expert – a beekeeper named Bill Simpson. He recognised them as fossil impressions, and contacted the Australian Museum. The palaeontologist they sent verified that they were fossils, and that they were from the Late Devonian, about 360 million years ago.

If you didn’t see anything fish-like in the slab, don’t worry – they’re negative impressions of the armour of armoured fish, so they’re nothing you would automatically recognise.

So, they took that slab away, and apparently no one thought to write down where they’d found it, because when the museum wanted to see if there were more of them, no one knew where the original site was. It was only in 1993 that the Canowindra fossil layer was finally relocated, and the subsequent dig confirmed the site as one of the greatest fossil finds in the world. About 200 rock slabs were recovered, with more than 3700 fish specimens, the remains of a single community. And that was only at the roadside – much more lie buried beneath the road itself, waiting for sufficient funding to re-direct the road.

The fossils themselves were probably formed in a lake, and there are some slabs that seem to come from the ‘shore’ because they have several fossils of juvenile fish, and then…nothing:

That’s a nice colour outline of where the fossils are. Now this is one of the slabs:

Some close-ups:

It’s not very clear, but you can see the pattern of the armour.

The way these fossils have been formed indicates that all these fish died together in the same mass-kill event, probably a sudden depletion of the lake. There are two main theories as to how that could have happened; the first, that a large freshwater lake supporting thousands of fish is struck by a severe, once-in-a-century drought, and as the water evaporates the fish are trapped, and they all die. The second theory is that some kind of disaster demolished a natural barrier like a bank or sandbar, resulting in the abrupt draining of the lake.

These are the kinds of fish found on the slabs:

The placoderms dominate, making up about 97% of the fossils discovered, while the sarcopterygians were much rarer. In fact, you see the one just one up from the bottom? That one’s called Canowindra grossi, because it’s only known from one specimen found on the original slab, in 1956. Unlike the other sarcopterygians, which are related to Devonian fish found in the Northern Hemisphere, it belongs to a separate family entirely. No other fossil of this fish has ever been discovered.

The original slab:

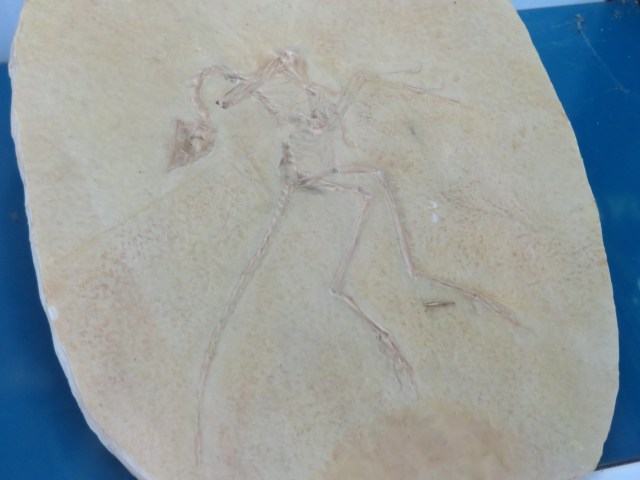

The Canowindra grossi specimen:

It’s hard to see in the negative impression, but they also used these to make fiberglass cast to get a ‘positive’:

Casts of some of the armoured fish:

This is what they think Canowindra grossi might have looked like:

And these are what they think the armoured fish might have looked like:

Yes, those little beads are the eyes – they were on the top of the head, surrounded by bony plates.

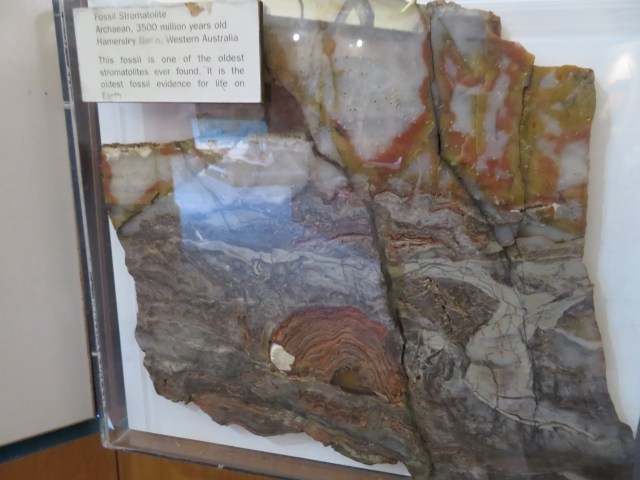

A fossil stromatolite:

This particular fossil is from Western Australia, and is 3500 million years old. Yes, 3500 million. It one of the oldest stromatolites ever found, and is among the oldest evidence for life on earth.

And what is a stromatolite? They’re created by cyanobacteria, forming mats over the surface of sediment. The bacteria secrete a sticky gel that traps the sediment, which gradually builds up and forms a raised surface and, eventually, mounds, that make up the stromatolite. You see, early bacteria first evolved when there was very little oxygen in the atmosphere, and produced energy using nitrogen and sulphur. But cyanobacteria evolved something different – photosynthesis. That way, with a little bit of water and a little bit of sunlight, they could create simple sugars to fuel themselves, with the by-product being a little bit of oxygen. It doesn’t sound like much, but over millions of years cyanobacteria raised the oxygen levels in our atmosphere, paving the way for the development of life as we know it.

And there are still stromatolites around, in Shark Bay in Western Australia.

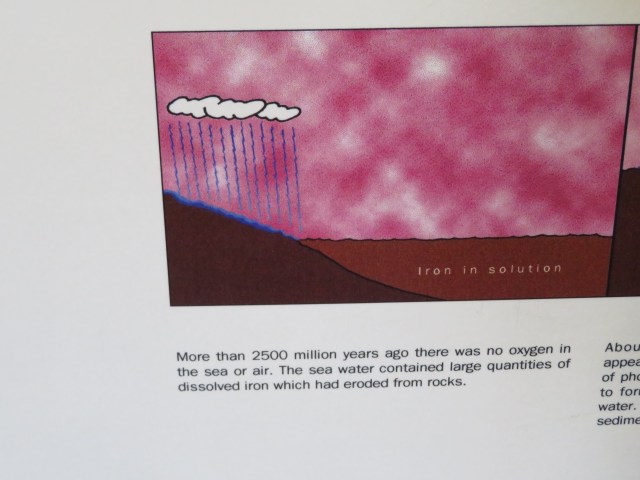

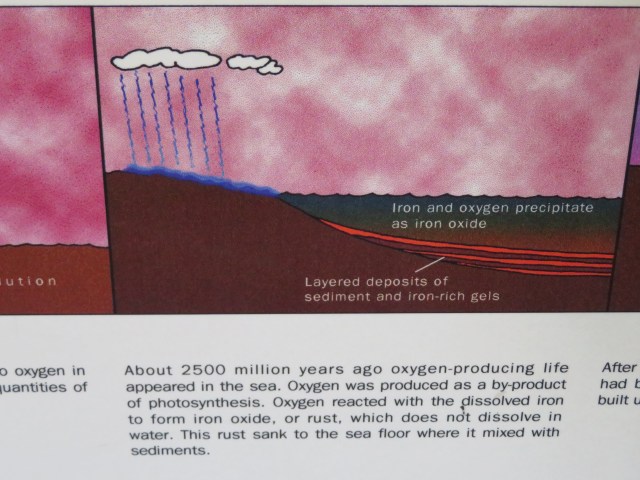

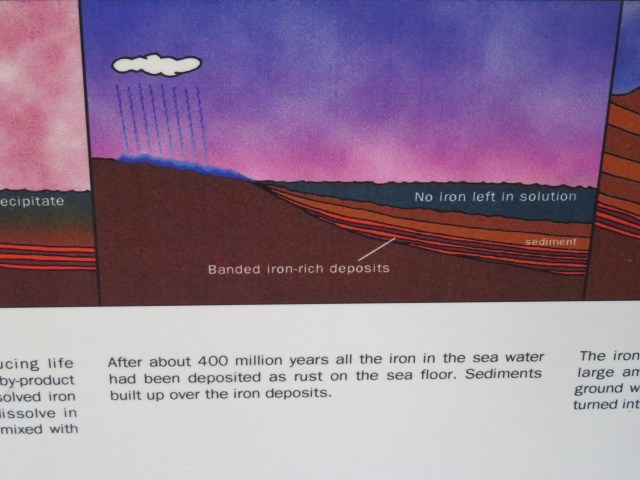

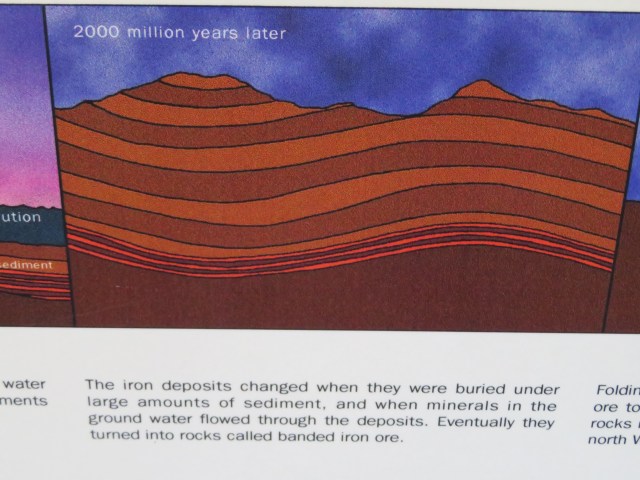

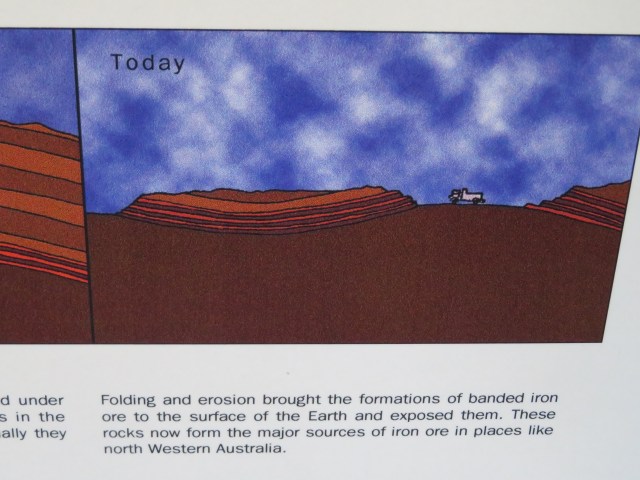

They also had the side-effect of removing iron from the sea – these diagrams explain how better than I ever could:

Once thing you can see in the pictures, but they don’t mention – the increase of oxygen and the elimination of sulphurous gas changed the colour of the sky from pink to blue.

And here’s some banded iron ore, about 2500 million years old, from Western Australia:

Back to the fossils. You see that bit that looks like half of an enormous fish?

It is, indeed, half of an enormous fish. Mandageria fairfaxi grew to over 1.6 metres long, and was the top predator of the lake. They’ve found impressions of its skull which indicate that it had backward-pointing teeth, and a jaw like a crocodile to hold onto struggling prey.

This is a cast of its head, compared to a turtle shell:

You can’t really see the teeth, so you’ll just have to trust me on that one.

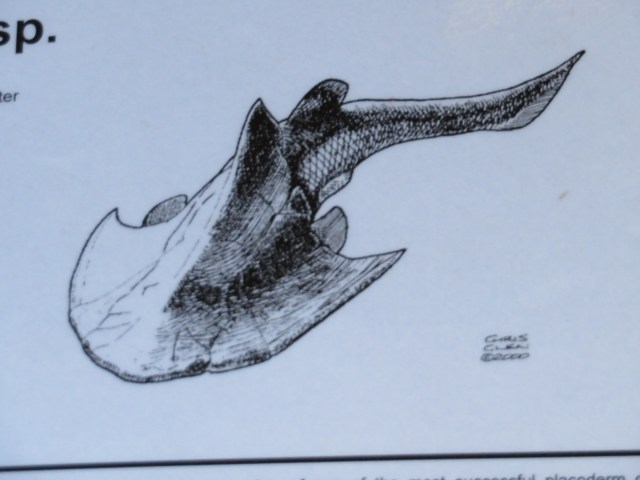

And this is Groenlandaspis:

Yeah, that little hole is its eye. This is what it might have look like:

It was a fish, but the armour makes it look a bit like a stingray. And these things were the reason the museum wanted to find the fossil site – because they have a widespread distribution, but not many good specimens had been found. So, when someone figured out that the Canowindra site might have some good ones, they went haring off to find it, and – as you might have guessed from the fact that you can spot an eyeball in the fossil up there – the excavation of the Canowindra site led to the best examples of Groenlandaspis ever found. Sometimes hunches pay off.

Now this is an impression of Soederberghia simpsoni:

Why is this special? Because this is a lungfish – common in Devonian rock, but very rare at the Canowindra site. It’s also one of the earliest known tetrapods (basically, anything with four limbs is a tetrapod, which essentially boils down to ‘all vertebrates other than fish’), and suggests there may be other tetrapod fossils still at the site, awaiting discovery. It also raises the tantalising possibility that perhaps there are so few tetrapod fossils at Canowindra because, when the water in the lake vanished and the other fish died, the tetrapods simply…walked away.

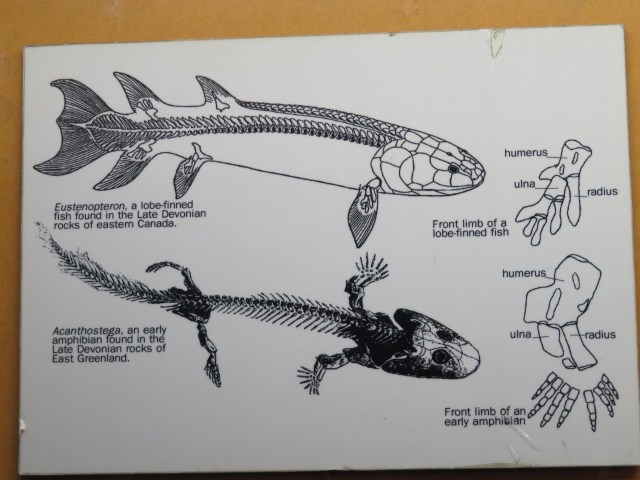

The museum also had some displays on fossils not found at Canowindra – this is a model of Acanthogestega, from the Late Devonian:

The long, flattened tail suggests this animal was wholly aquatic, but as you can see it possesses limbs and distinct (if webbed) digits, and palaeontologists believe this suggests that limbs and digits first evolved in water, not on land.

In comparison with Eusthenopteron foordi, a fish whose limb-like fins and two-way gill/lung respiratory system eventually gave rise to the terrestrial vertebrates:

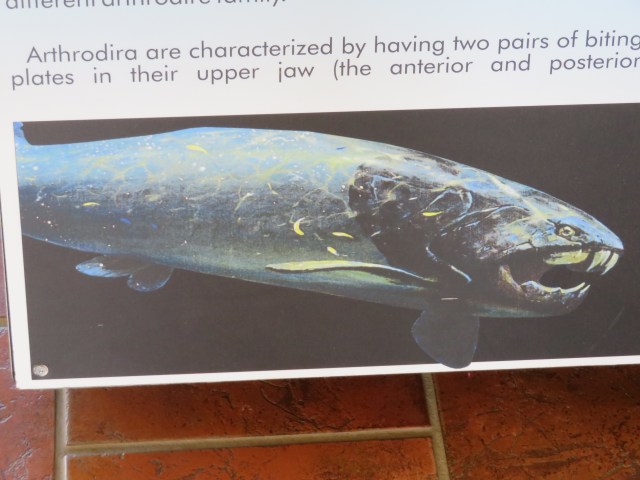

They also had a model of the skull of Dunkleosteus terrelli, a predatory armoured fish that was 3-4 metres in length:

This is what they think it looked like:

Beside another museum-goer for scale:

So, in spite of the fact that it looks like it’s wearing the kind of fake teeth people use for cheap Halloween costumes, this would have been the equivalent of a Great White Shark – not to be messed with.

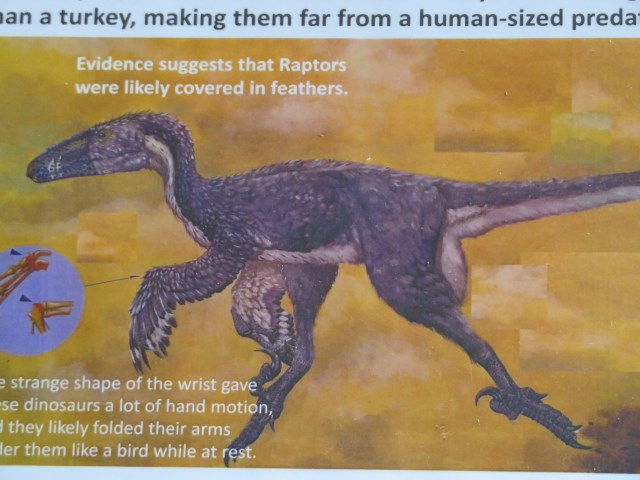

They also had some raptor models:

For scale:

Despite what Jurassic Park told us, velociraptors were actually the size of that little wooden model. They could probably still be dangerous in a pack – even if they are knee-high, a dozen of those things could still do a fair bit of damage – but I guess the movie-makers felt they wouldn’t be as menacing if it looked like the raptors could be sent on their way with a decent kick.

The bigger model was about as big as the raptors ever got, but the model is inaccurate, as recent evidence suggests raptors were covered in feathers, like this:

You can see why no-one has tried to make a ‘remastered’ Jurassic Park with more accurate dinosaurs. That looks less ‘menacing predator’ and more…well, ‘silly pet’.

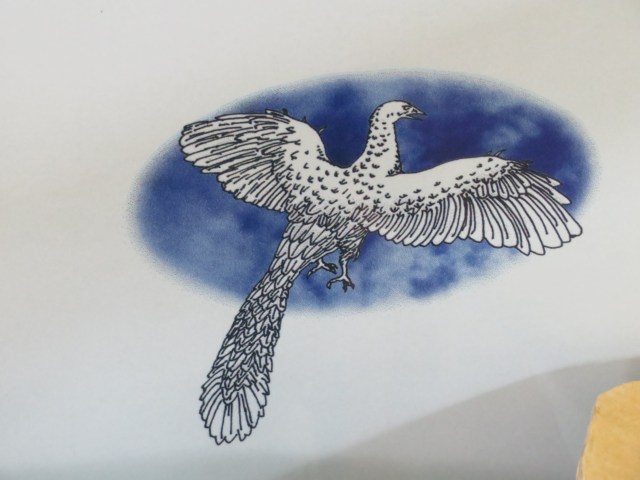

Speaking of feathers…this is Archaeopteryx, one of the first birds:

This what they think it looked like:

And from there, dinosaurs evolved into birds and, after the Cretaceous extinction event, the Age of the Mammals dawned. But Canowindra isn’t known for their mammalian fossils, so there wasn’t much on that.

Then I took off for the Canowindra International Balloon Challenge. The Challenge is actually held over several days, with various hot air balloon teams competing in several different competitions, but I only saw this day, where the objective was to hit some targets – basically, there were some targets in parks and properties outside Canowindra, and the people in the balloons were supposed to drop bags as close to the targets as they could get. I didn’t see that part, but I did see them set up.

First, a whole bunch of people with trailers hitched to their cars pulled up in the park:

I only realised they were hot air balloons because of the basket – everything else was tucked away. The gigantic ‘balloon’ part of the equation was folded up in a bag, and it had be to unfolded:

And the baskets were tipped on their side so they could be hitched up to the balloon:

They had an announcer telling us about the teams, and there were some international teams, and some from universities, but a lot of them were basically ‘an enthusiast from down the road with their friends and family’. Though I suppose that makes sense – if you live around the place where they host the International Balloon Challenge, you’d be more likely to be interested in balloons than a random person from the other side of the country.

They also a lighter-than-air blimp overseeing everything:

As you can see, it’s from a television station, and there’s a camera attached to it.

While they were hitching the balloons up, the baskets were also attached to the cars – you can see it pretty well in this photo:

Nothing complicated, just an anchor. Because the next step is what the announcer called ‘cold inflation’, when the balloons are inflated with fans:

Then the balloonists position their gas burners, and inflate until the balloon is upright:

Have a picture, too:

Most of them were inflating at about the same time:

I got a picture of the flames in one of the balloons:

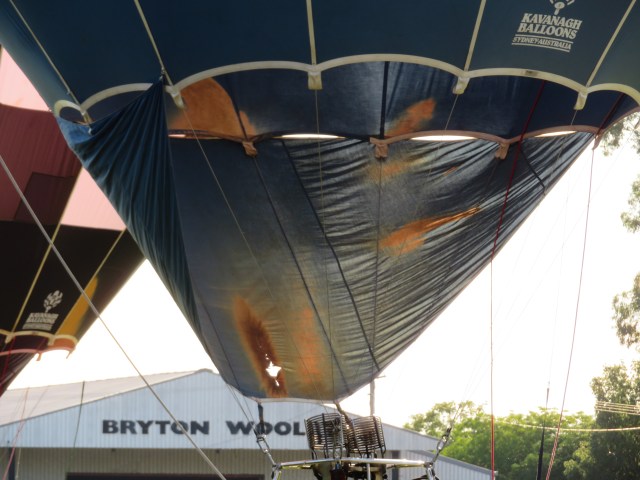

As you can see, they were pretty substantial jets of flame – some of the balloons had scorch marks on them:

Yeah, there’s a reason they go up with a fire extinguisher. I also noticed that all the balloons had letters on them:

As some kind of registration. Which I never even thought about, but makes perfect sense – it’s a vehicle (of sorts), so of course it has to be registered. I mean, I had to register my caravan, and that can’t move under its own power.

This was the first balloon in the air:

I took a video, so you can appreciate how fast it was rising:

You wouldn’t think it, but they can really shoot up.

Some more balloons on the ground:

You can see some still inflating in the background of the last photo.

Some more lift-offs:

Drifting upwards:

It was quite interesting to see them go, because even though the pilot can control the height of the balloon, they’re at the mercy of the winds.

I took a video of one of the lift-offs – you can see them unhitch from the car as they go:

The ones still waiting on the ground:

Another lift-off:

By this point, a lot of them were just little coloured dots in the sky:

At this point, they seemed to be almost still – you could only see them moving if you looked at them in relation to each other:

When they were all little specks in the sky:

I headed back to Turtle Shell. I’m really glad I arrived in time to see the balloon challenge – I’ve seen hot air balloons in the air before, but I’ve never seen them set up.

The fossils are great – although INFORMATION OVERLOAD 🙂

I love the dog sized velociraptors – Hollywood never let the truth get in the way of a good story (Great Escape, U571).

The hot air balloons are impressive, and so colourful.

LikeLike

What was marketed as ‘Velociraptor’ was probably Deinonychus – they’re about the same size, body shape, etc. of what was in the movie, but I guess Velociraptor sounds scarier. Deinonychus sounds like an obscure dental problem…

LikeLike

Great fossils- scary big fish with big teeth. Glad it’s not around now! Also great to see balloons.

LikeLike

The balloons were pretty amazing. I’ve never seen that before.

LikeLike