Today, I took a tour of the Cathedral Cave and the Phosphate Mine out near Wellington.

Originally, the zoo was going to be my first stop, but I made the mistake of trying out a new exercise regime involving squats on Wednesday, and my legs still hate me for it. So, I decided instead of walking around a gigantic zoo, I’d take a walk around a large cave (it’s smaller than the zoo, though – it makes sense!).

It was about an hour’s drive through some light rain, and I spotted this as soon as I got out of the parking lot:

It’s a Diprotodon! Fitting, given that this site was the first place Diprotodon bones were ever discovered. When I arrived, I was still half an hour early for the tour, so I checked out their aviary:

They had a lot of birds in there – and very colourful ones, too. I got some photos (any fuzzy lines through them are the out-of-focus bars).

A crimson rosella:

Australian ringneck:

These are various colours of the Indian ringneck:

Red-rumped parrot:

You can’t see its rump, so I’ll let you use your imagination for that one.

Sulphur-crested cockatoo:

Regent parrot:

Australian king parrot:

I also took a video of one of the ringnecks and the crimson rosella foraging on the ground:

I’m not sure if that’s strictly foraging or something else, but I’m going to say foraging until someone tells me different.

Then the tour began – to Cathedral Cave! First, our guide explained about the landscape – it’s technically called kast, because it’s made of limestone.

All those rocks are limestone, remnants of a coral reef that was there when Australia was still part of Gondwana, and this was under the sea. Which is kind of crazy to think about, but there you are.

On the way to the cave entrance, we stopped at a place called Mitchell Cave:

As you can see, it’s closed off now, but it used to be a paleontological dig site, and is where Major Thomas Mitchell discovered the first Diprotodon bone. According to my guide, it happened when he was trying to go deeper down into the cave, so he tied a rope around what he thought was a rock. Except when he tugged on it, the ‘rock’ popped out of the ground and he realised it was an enormous bone.

That’s seems a common theme with these ‘first discovery’ stories. You think it’s all skill and training, but most of it seems to be luck and talking to a person who actually knows something about ‘the thing I tripped over on the farm – you think it might be something special?’ Makes you wonder how many ‘first discoveries’ didn’t happen because someone shrugged and threw the weird thing out instead of asking about it.

Anyway, back to the point – this little cave was where the first Australian megafauna fossils were extracted in 1830.

This is an excavation shaft that descends to the end of the cave:

This was dug in 1881, basically to make sure they’d pulled up all the fossil material they could.

We also passed a model of Megalania:

Basically, think of a giant goanna that could have eaten you. They think this might have been around when the Aborigines were, which would have been…interesting…to say the least. Although, given what else humans have hunted, it’s entirely possible they looked at that thing with enormous teeth and claws and thought, ‘That is big enough to be breakfast, lunch and dinner. Get the spears, we’re eating giant lizard for the foreseeable future.’

Finally – the cave entrance:

It was a tiny little door and some slippery stairs into the dark. Fortunately, there was a handrail. It was amazing how quickly the temperature changed, as well – the caves are 17-18oC all year, and it isn’t a gradual gradient – once you’ve gone five metres into the cave, it’s suddenly much cooler.

I took this photo facing back towards the entrance:

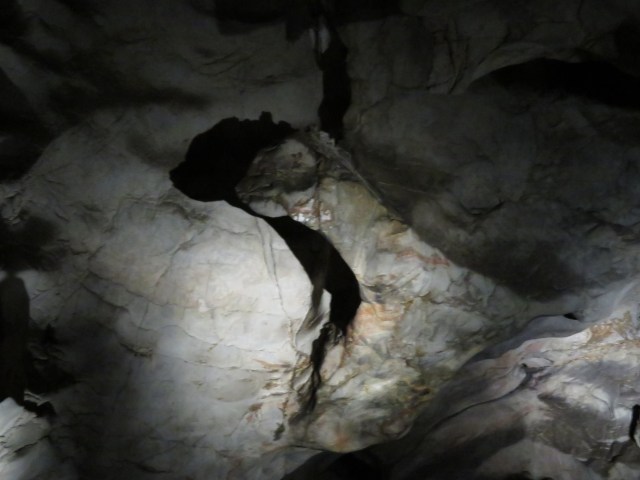

This is a photo of the ceiling – more specifically, of a stalactite:

This is a formation called the Dragon, because it looks a bit like a dragon’s head:

Or a dinosaur’s head – could be either, really. To me, the shadow looks better than the actual formation. By now, we had left the stairs and were walking on clay, which was strangely sticky.

There was also old graffiti on the cave walls – not the kind you’re thinking of, with spray paint, but the kind done by people who brought candles to explore a cave. They’d burn their initials on the wall with the candle:

Some spots were more popular than others:

The entrance to the ‘cathedral’ part of Cathedral Cave:

We walked into it in darkness, and the cavern gradually lit up. I took some bad video:

And some equally dark pictures of one of the largest stalagmites in the world:

This was another reminder of how eyes are awesome. There were lights in the cave, which meant the camera couldn’t strike the right balance, even with the flash, but everything was perfectly clear to my eyes.

This was looking up at the ceiling:

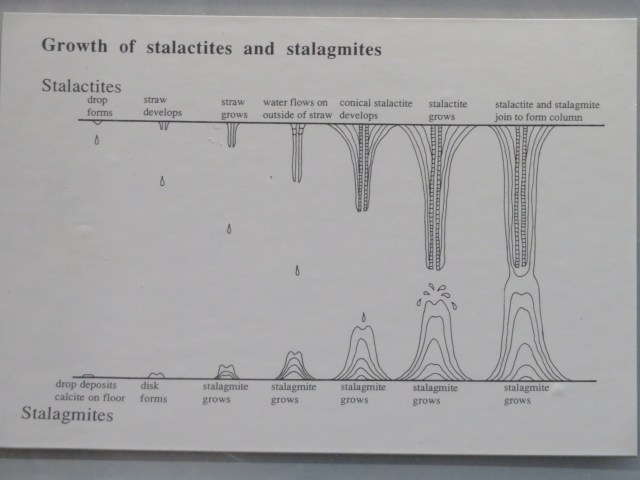

Big scientific explanation, coming up! If you’re not interested, just skip to the next photo – you won’t be tested on anything here. Unless you’re taking chemistry or geology, in which case – study up!

The caves were formed by groundwater slowly eating away the limestone. Rain is slightly acidic, and once it becomes groundwater it becomes more acidic, enough so that each rainfall would have dissolved a thin layer of the stone, eventually forming the caverns and various rock formations within. How long it took is still unknown – caves are difficult to date, because you need to know when the rock was removed, not when it was formed.

A cave must be younger than the rock in which it was formed, but older than the oldest material filling it. It’s known that the Wellington caves are over 10 million years old, but just how much older is up for debate. The limestone itself hails from the Devonian period (often known as the Age of Fish, when plants were just starting to spread across the land), so it’s somewhere between 390-386 million years old.

The stalagmite was created by water, too. You see, as rainwater trickles through the rock on top of the cave, it picks up carbon dioxide and minerals from the limestone, mainly calcite. When the water comes into contact with the air inside the cave, it wants to reach equilibrium with it. The carbon dioxide escapes the water, and without the gas, the calcite precipitates out, depositing a tiny amount of calcite – basically the rock stuff – where the water emerged. Eventually, the calcite’s length and thickness increases, becoming a stalactite.

Stalagmites form beneath stalactites, as the water dripping from the end of the stalactite deposits more calcite in a mound. Here’s a nifty diagram:

Also of interest – the inside of a stalagmite:

I took that photo in the visitor centre afterwards. It really shows you how it forms in layers.

So, that big thing up there is basically a giant stalagmite, but there’s a lot of flowstone as well. Flowstone is formed by sheets of running water, often with little ridges as the water deposits calcite when it flows irregularly.

It had rained recently, so there were recent deposits on the stone – they’re the bits that look shiny and sparkly in the pictures.

Me, in front of the Cathedral:

Remember how I was talking about stalactites earlier? (Or, if you skipped it, never mind.) These are little baby stalactites:

At this stage, they’re called straws.

The disc of a stalagmite forming beneath them:

Another angle on the Cathedral:

You can actually see where water ran off the stone, filled a small well beneath it, and then overflowed to keep on running down the rock.

Close-up of the well:

Part of the cathedral wasn’t shiny and sparkly, because there hadn’t been enough rain for water to wash over that part and deposit a new layer:

I tried to capture some of the sparkle:

Before it was protected in 1884, people actually broke off parts of the Cathedral and took it home with them – this is a picture of a chunk that’s missing:

Over a hundred years later, and it’s barely changed. Really emphasises how long it takes to make something like the Cathedral. Even those baby stalactites are probably older than me.

This was at the side:

That is the site of a genuine palaeontology dig. Apparently a nearby university excavated quite a few fossils before their funding ran out – our guide even showed us some of them. Mainly little jaw bones and teeth and the like.

We set off further into the cave, down a metal stairway until we arrived on clay again. Our guide pointed out where part of the cave had collapsed a long time ago:

Basically, this is the fate that awaits all the caves, eventually. Rain and groundwater will wear the ceiling too thin, until it just gives way and buries everything. You can see that it’s different rock to the rock of the caves – it’s conglomerate, rather than limestone.

Another photo:

In this one, you can see the way the layers of rock have folded and shifted. At some point, this part was a lot deeper in the Earth’s crust – not deep enough to turn to marble, but deep enough that the limestone became malleable and started to fold. Then it came up close to the surface again, because geology has mysterious ways.

A close-up to show the bricking:

This is what happens when water runs down layered limestone – it doesn’t run evenly, so gradually carves little indents and make it look like layered bricks instead of rock.

All of this was in a little cavern below the Cathedral. I took a photo looking up at it before we moved on:

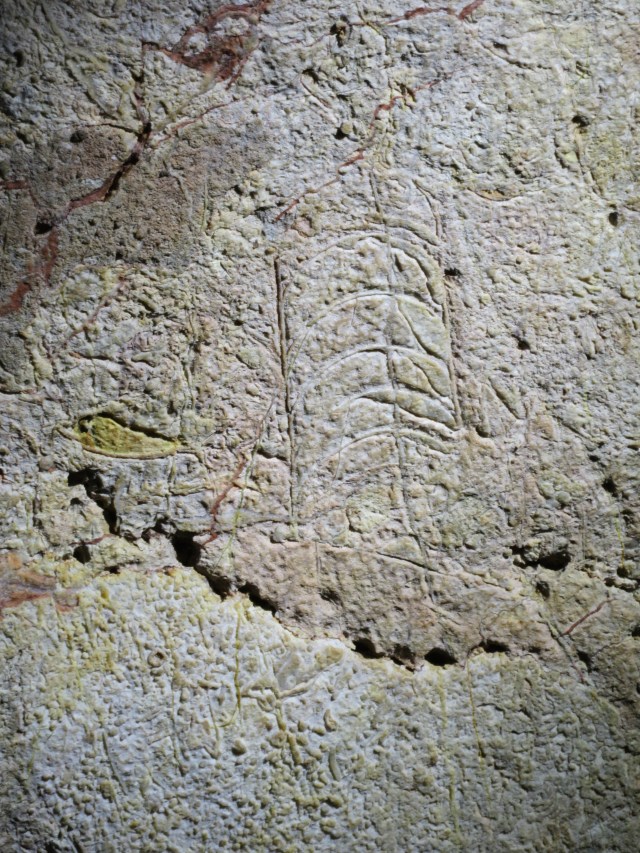

If you look at the ceiling, you can see more of the candle graffiti. Here’s a closer look:

That’s supposed to read Jo Sibbald, made by James Sibbald, the first caretaker of these caves. There were quite a few other places with his name. Now, you might be wondering why a caretaker was going around putting his name over everything, because that doesn’t seem like something they should do, does it? That’s because he didn’t become the caretaker by handing in his resume, he was just the guy who was already giving tours of the cave, so they decided to make it official. A truly inspiring tale in the vein of ‘fake it ‘til you make it’. The moral of this story is that if you act like you know what you’re doing, people will believe you.

Attention! I have been corrected by those more well-informed than myself that this is actually a signature of John Sibbald, the eldest son of James – you may note that the ‘S’ is back-to-front, and is the only ‘S’ like this in the cave. Thanks to Vince Sibbald, a helpful descendant.

Then it was time to go deeper into the cave. Have a dark photo:

The guide called this Headache Rock, and it’s a tricky one. It’s obvious you need to duck, but what tends to get people is the overhand behind it that you can’t see – I had to keep my head down until I passed a white line painted onto the floor.

Then our guide used his torch to highlight this section of rock:

Nothing special, right? Look closer:

See those lines that look like segments? That’s a fossilised nautiloid in the limestone, from that Devonian period I mentioned earlier.

This is the well:

As you can see, it’s a pool of beautifully clear water at the lowest point of the caves. The water level is variable; sometimes it rises enough to flood the caverns, and sometimes it’s completely dry.

I took a video of a water droplet falling into it:

This isn’t a big cave-diving spot, but there are other places in the Wellington complex that are famous cave-diving experiences. McCavity is known for being pretty amazing, and it was there that these creatures were found:

These are tiny crustaceans known as syncarids, and are a living relic from 100 million years ago, when these kinds of animals would have lived in surface waters. They probably went underground as Australia dried out, following the water.

I found these near the well:

These are rimstone pools, and they form when running water passes over an irregularity and deposits calcite.

Finally, we climbed the last set of stairs to the Thunder Room:

On the way up, our guide pointed out a white arrow painted on the rock, pointing to what looks like a face:

Seeing faces like this is called pareidolia, and occurs because our brains are wired to look for human faces. So, if it receives stimuli that comes close to the arrangement of facial features, it imposes a face. Man, this is such an educational post today.

A picture of some of the formations in the Thunder Room (also, a random guy’s face):

That’s not pareidolia, he was actually there.

The ceiling:

Now, I’m sure you’re wondering why it was called Thunder Room (and if you’re not, then too bad – I’m going to tell you anyway). It’s all to do with this little corner:

Basically, Thunder Room had some crazy acoustics – step into that corner and even a little hum sounds like a plane touching down.

Then it was time to retrace our steps and go back into the sunlight (I resisted the urge to hiss like a vampire). It was half an hour until the next tour I’d booked, so I got some lunch in the little café there while I was waiting for the Phosphate Mine Tour:

The mine:

Inside:

We all had to wear hardhats to go inside, because it was a genuine mine, so there are certain safety regulations that have to be met.

The white stuff is the phosphate:

This mine was opened during World War I, when phosphate was needed for explosives. It closed shortly afterwards, because without a war to drive up the price, it wasn’t commercially viable. So basically, this place has been a tourist attraction for much longer than it’s been a mine.

Also, phosphate is usually found in bird and bat faeces, so they were mining centuries-old bat poop.

This is how it’s usually found – layers of sediment, calcite crystals, and the phosphate is on the bottom:

Given that it was a mine, there were several shafts to the surface:

Just below that one was this pit:

That wasn’t used to dig phosphate – it was a sink shaft. Basically, where a weight was lowered to bring up a bucket of phosphate.

A natural shaft:

All those shafts mean that the mine is home to birds and bats. I got a picture of this welcome swallow:

Looking up the natural shaft:

They had some remnants from the old mine, including the tracks they would have hauled the carts on:

Because the mine was much closer to the surface than the cave (and with earth above us instead of stone), tree roots often made surprise appearances through the ceiling:

A tunnel that got flooded and choked with sediment:

A man-made shaft:

A lot of places had the old wooden props and beams:

There were calcite crystals on the walls, and while they didn’t sparkle as much as in Cathedral cave, they still twinkled nicely:

Another relic – an old mine cart:

See the long scratches in this one?

That’s a photo of one of the walls, and those marks were made by pick-axes when the mine was operational.

At this point, we were walking through a tunnel in the dirt:

The lack of reinforcing was interesting – I’m not sure why this point was stable when others weren’t (mysterious geological reasons, I guess), but there was a small, exploratory tunnel that had some props:

No, we didn’t go down that one, though I’m sure that would have been an interesting exercise.

We came into a small dome, one side supported by a square of stacked logs:

A photo of the dome:

You see those little white flecks in the dirt? That isn’t phosphate.

They’re bones! This called Bone Cave, and it’s where most of the bones of the megafauna have come from. Some of the bones are 300, 000 years old, and most of them were carried in by repeated floods.

The bones in Bone Cave were first excavated by German scientists, just before World War I. When they were told to return to Germany, they asked their two Australian assistants to continue excavating, and send what they found to Munich. The dome was formed when one of the assistants decided that to take a shortcut – instead of digging everything out, he’d just blast it out!

This is the recoil from an explosive charge:

Definitely not accepted practice today, but they did get the bones out, which is why some bones from this cave are on display in Munich.

Along the passage, there were models of various skeletons that have been found in the caves:

That’s Thylacoleo, the marsupial lion. Again, this was first discovered in the Wellington caves. Next up:

Diprodoton! You already know the story of this discovery.

Another life-size model:

This is Wamambi, a snake over six metres long, and what some believe may have been the inspiration for the stories about the Rainbow Serpent.

With people around for scale:

Again, these bones were first discovered in Wellington Caves.

I’m wondering why this isn’t more widely-known. I mean, it’s barely advertised – I had to go on a tour to find out that an hour away from Dubbo, there’s a cave riddled with bones that first let people know this continent used to be inhabited by even more animals that could ruin your day.

I say ‘even more’ because I think everyone generally understands that Australia is already inhabited by a lot of animals that can ruin your day.

The tunnel that led us back to the entrance was supported by wooden planks and arched metal:

Yeah, it felt like walking through an enormous barrel. Then I was out in the daylight again.

Before I headed home, I took the fossil walk – just a little marked path through a bunch of rocks that have fossils in them. I took photos of the interesting ones. These are fossilised coral:

This is the shell of a nautiloid:

The nautilus we see today have spiral shells, but Devonian nautiloids had cones.

These are shells of marine snails:

This isn’t a fossil – just a downed tree. I took photos because I thought it was interesting to see how the tree had started to hollow before it toppled:

Back to the fossils! More coral, all the coral:

This looks like a worm of some kind, but it’s actually Favocites, a tabulate coral:

More tabulate coral:

Crinoid (sea lily) stems:

I also dropped in on the visitor centre to take a photo of this Diprotodon skull:

It’s not a real skull, just a cast – the real one is in the British Museum.

Then it was back to Turtle Shell. Tomorrow, I go to the Warrumbungles!

I feel edumacated….

LikeLike

I am so smart! I am so smart! S M A T – I mean, S M A R T! I am so smart…

LikeLike

Loving the caves! I, too, now have a slightly larger brain.

LikeLike

They were fantastic! And as I have noted, the tour guides were very informative. Good thing I wrote it down here, so I’d have forgotten all about this in a few days.

LikeLike

You were incorrect about the signature it is not JO for James but JO for John the eldest son of James who was my Grandfather you might notice that the S was back the front as well and this is the only back the front S in the caves. But the rest of write up was excellent.

Regards Vince Sibbald.

LikeLike

Thanks for the correction! I’ve edited the post to include it.

LikeLike