Today’s agenda was a long trip to Narrabri, specifically the Paul Wild Observatory.

There was a lot of wind and some rain on the drive – I was moving parallel to a storm front:

Took that photo while I was stopped at some roadworks.

As the title says, the observatory is home to the Australia Telescope Compact Array, used for radio astronomy. They had a bunch of signs up on the driveway warning you to turn off all transmitting devices – phones, radios, even microwaves – because they would interfere with the telescopes. The wind was pretty crazy when I got out of the car, and there was a flock of galahs screeching too:

The actual telescopes:

As you can see in some of the pictures, they’re on rails that look like train tracks, so their positions can be adjusted.

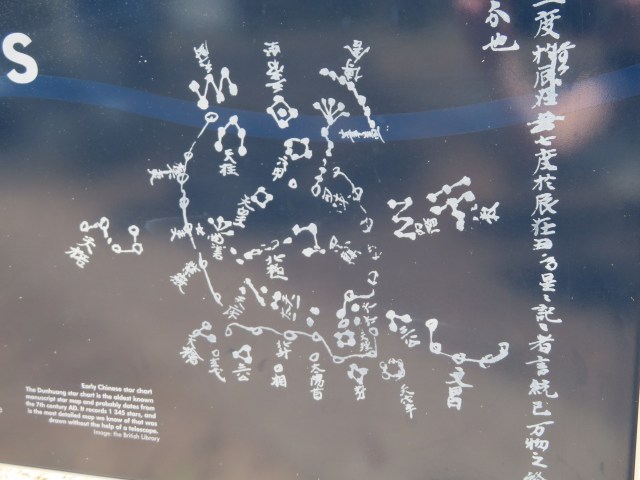

They had a lot of informative signs around the place, so have a photo of an early Chinese star chart:

They also had a simple radio telescope that you could adjust:

They had an attached dial, too:

So you could see exactly how strong the radio waves were. They recommended you point it at the sun – the strongest radio source in the sky. I’d just done that before taking the picture, which is why the reading is so strong.

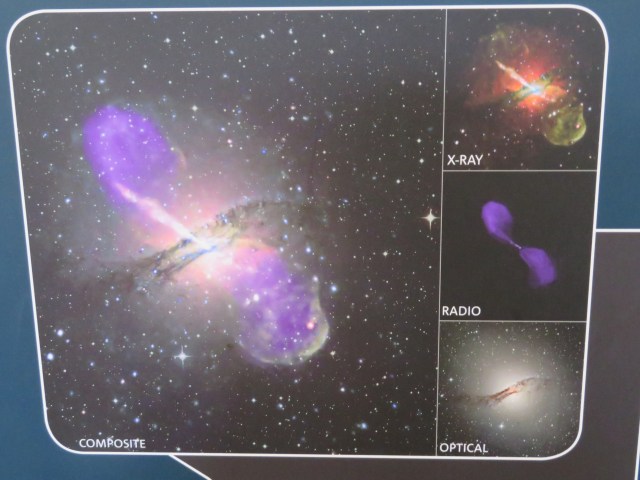

Now, radio telescopes only pick up radio waves – they don’t pick up light like optical telescopes – and they’re mainly used to detect stuff like giant gas clouds between stars or jets of particles spat out by stars and black holes. For example, this is a composite picture of the galaxy Centaurus A, achieved by combining optical, radio and X-ray images:

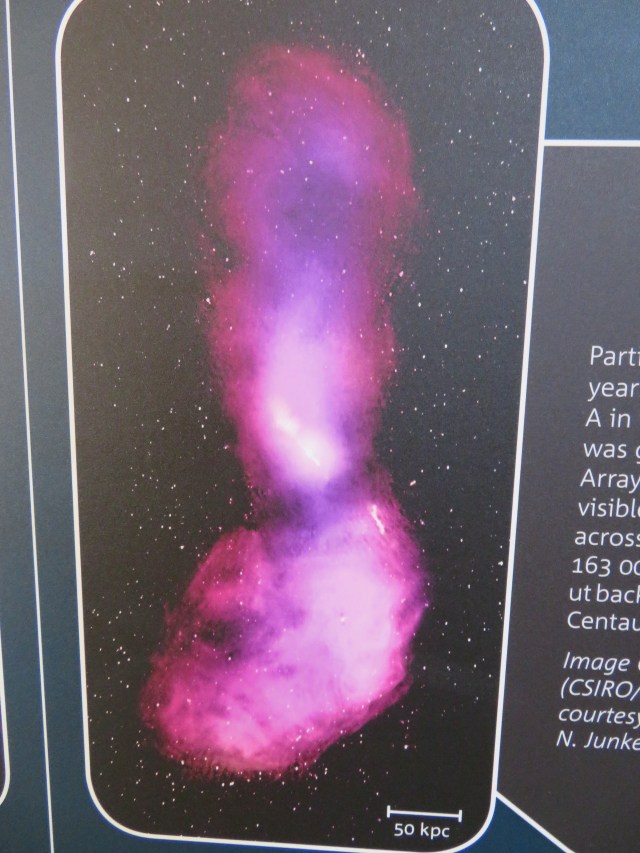

This is the radio image of the Centaurus A galaxy:

Because this is radio, not optical, those pinpoints of white aren’t stars, but background radiation sources. This means each little dot is a galaxy.

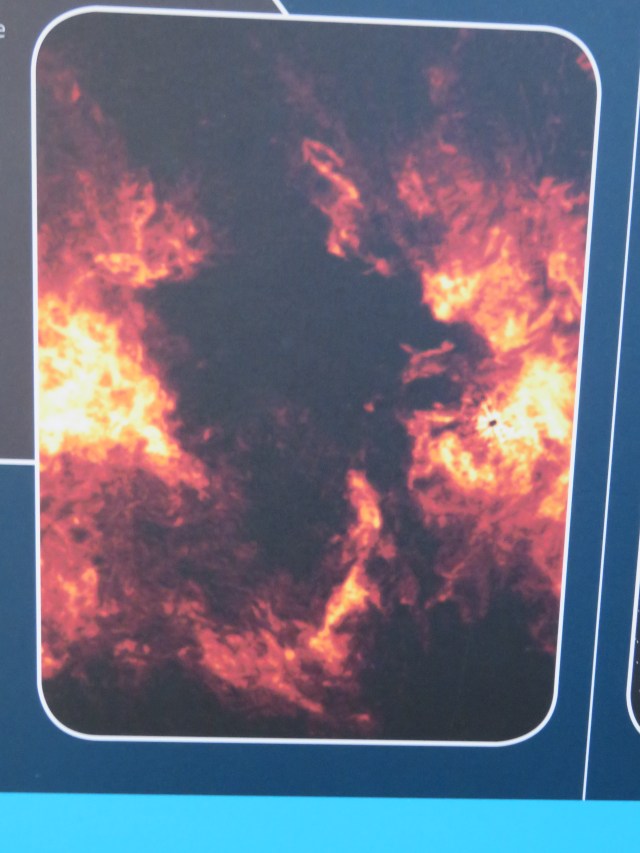

Radio telescopes can also help find holes in the galactic plane. You see, a lot of our galaxy is made of warm atomic hydrogen gas, just hanging around, but there are lots of holes in it. This is a picture of the structure called GSH 277+00+36:

Basically, that’s a void in the hydrogen more than 2000 light years across. A hole hundreds of times bigger than our solar system – pretty freaky, huh? They think it was formed by the supernova explosions of about 300 massive stars over the course of several million years. Eventually, the void grew so large it broke out of the galaxy disc, forming a ‘chimney’. This is one of only a few chimneys in our galaxy, and the only one known to have exploded out of both sides of the galactic plane.

This is Pictor A, a radio galaxy:

That’s a composite picture, by the way – radio and X-ray. That blue line is an X-ray jet being shot out from the centre of the galaxy, across 360 000 light years.

Radio galaxies emit large amounts of radio energy (which I’m sure most of you guessed). Each one has a massive black hole at the centre, the presence of which is revealed by jets of particles shooting out of the region around it. The early universe was full of giant radio galaxies, but they’re very rare now, and usually so far away they can only be detected by the jets of expelled matter.

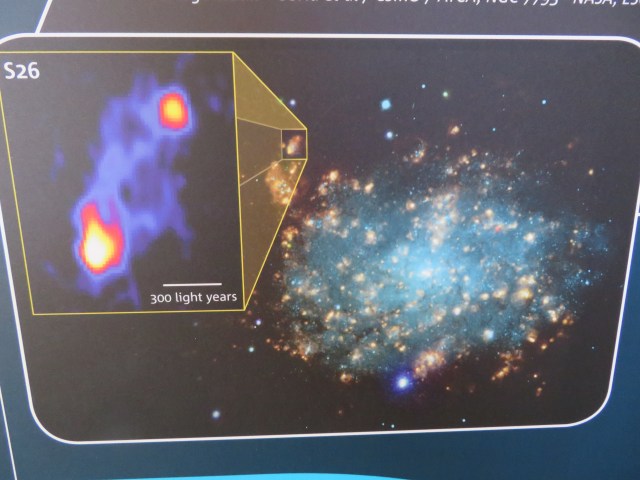

The miniature quasar S26 in the galaxy NGC7793:

Quasar is short for quasi-stellar radio source, and they’re basically radio galaxies with really bright and active centres. The most luminous things in the universe, they’re also the most distant objects in space we can see from Earth in visible wavelengths, but they’re so far away they just look like faint red stars.

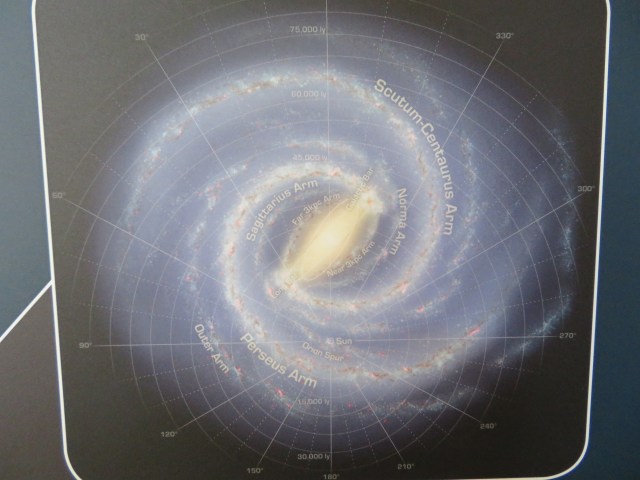

A map of the Milky Way (based on our current understanding):

The lines all helpfully lead to the little circle that encloses our sun, on that tiny little spur on one of the arms.

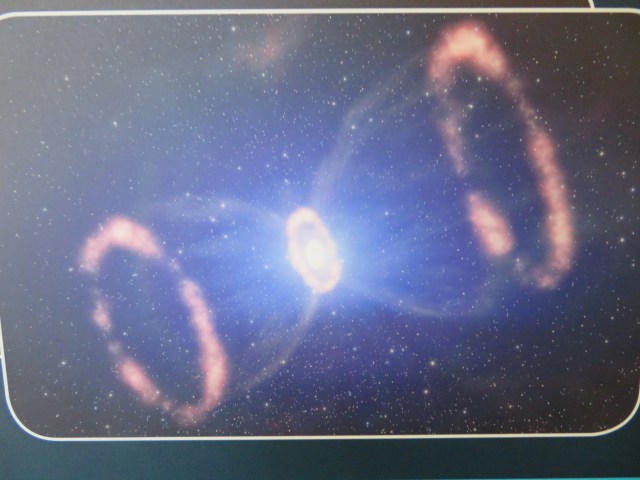

Artist’s impression of Supernova 1987A:

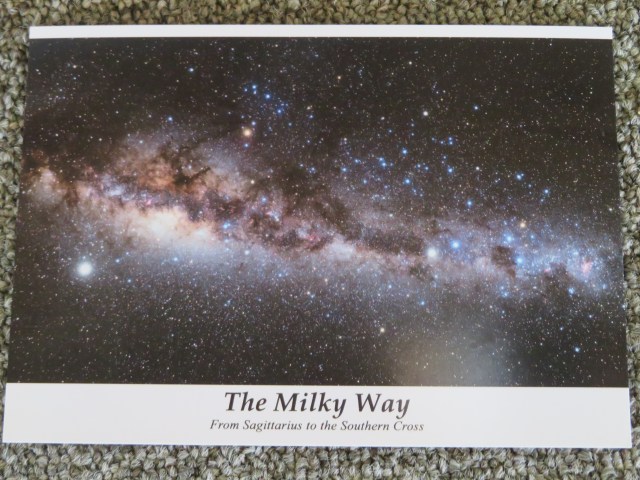

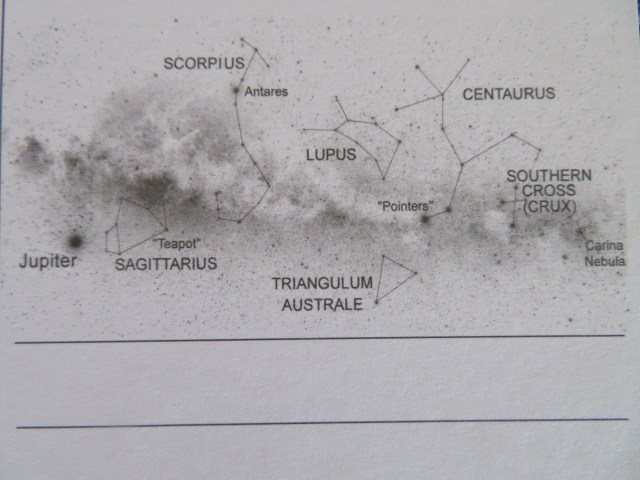

The Milky Way, from Sagittarius to the Southern Cross:

Star map for the above (because I certainly didn’t recognise anything):

Low-noise amplifiers:

Basically, these magnify weak signals received by the antennae. To enhance performance, they’re cooled to truly ridiculous temperatures – below 250oC.

Science, man. It’s crazy.

Then I headed back to Turtle Shell, and I’m typing this just as the storm has hit Tamworth – there’s thunder, lightning, and rain outside, but I’m feeling very cosy. Ancient humans’ decision to get out of the weather was probably one of the best calls ever.

Ancient wisdom

LikeLike

Pretty amazing, huh?

LikeLike